Abstract

The unexpected outburst of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA in March 2020 hit small businesses across the country, triggering mass job losses and closures. Beyond the severity of the pandemic itself, policy responses adopted by state governments produced yet another set of changes in small business operating environments. Using data from the Small Business Pulse Survey and the Current Population Survey, this paper provides evidence of how small businesses experienced these policy changes during the first few months of the pandemic in terms of perceptions of the pandemic, adjustments in employment levels, and employee schedule, as well as changes in overall self-employment activity. Policy variables include the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and a State Orders database. We find that the PPP per firm on the state level has a strong positive impact on lessening firms’ negative perceptions, alleviating the need to downsize, and recovering self-employment activities. The lifting of shelter-in-place, non-essential business closures, and restaurant dine-in services restrictions all helped, though their impact was more modest than PPP’s. The magnitudes of both effects vary by industry and owner groups.

Plain English Summary

Policy responses enacted at the state level during the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impact small businesses’ recovery. This study explores how state reopening policies and the PPP impacted small businesses’ reactions to the pandemic, including their perceptions, workforce reductions, and self-employment activity. We find that the PPP amount per firm by state is significant in alleviating the negative impact. State-level policy responses vary in their scope and timeline, and we find that these policy environments (shelter-in-place, non-essential business closures, and restaurant dine-in restrictions) shaped business recovery activities. These effects vary by industry and owner groups. More research is needed to identify the access barriers of different groups to business support, and to evaluate the longer-term effect of these policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this research is publicly available. Replication files can be obtained from the authors.

Notes

We also note that individuals with self-employment income were eligible for PPP, provided that their activity was in operation by February 15, 2020, they filed a Form 1040 Schedule C for 2019 or 2020, and their principal place of residence was the USA.

Pulse data is released as aggregated tabulations of each possible answer to each question, such that it is not possible to observe individual firms. For interpretation, a decrease in the percent of values that reduced employment suggest an increase in the share of businesses that either increase employment or did not change it.

The database compiled by Goolsbee et al. (2020) also includes information on local level policies. However, we are not able to leverage these as the datasets (Pulse or CPS) do not identify areas smaller than states.

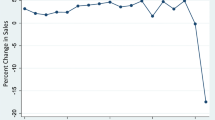

Combining the Pulse weekly data into months would make it more comparable to CPS but at the cost of significant information loss in weekly variation. Therefore, we opted to keep each data source at its original periodicity. We use all weeks available on Pulse phase 1 (weeks between April 26 until June 27) and restrict CPS to the months of April until August, when the number of businesses increased to pre-pandemic levels (Fig. 3), and the number of new cases in the USA started decreasing.

Using the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases until the current week or month rather than new cases does not change the conclusions regarding the policies’ impacts significantly. However, in understanding that policy decisions, business perceptions, and decision-making (especially during the first phase of the pandemic) were guided by the current severity of the pandemic, we adopted new cases as our preferred specification.

The CPS analysis excluded the following industries: public administration, agriculture, forestry and fisheries, mining, and wholesale trade. Public administration had no active self-employment, and mining and wholesale trade had self-employed workers in only 8 and 31 states, respectively. Finally, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries were excluded for consistency with Pulse, which focuses on nonfarm businesses. For a detailed overview of the relevance of self-employment as a share of total employment across industries, see Table A1 in the Supplementary Information file.

The weekly Pulse data does not include information for all industries consistently across states and time, and the reasons for the omission are unclear. In our analysis, we kept only industries that were present in at least 70% of the state-time periods in Pulse phase 1, namely those that appear in the data at least 321 times out of 459 (9 weeks × 51 states). Based on this criterion, the Pulse analysis features the following eight industries: professional, scientific, and technical services (434 observations); health care and social assistance (424); retail trade (413); wholesale trade (393); manufacturing (385); construction (356); other services (except public administration) (338); and accommodation and food services (329). Conversely, the following nine industries were excluded: finance and insurance (301); administrative and support and waste management and remediation services (301); transportation and warehousing (245); real state and rental and leasing (224); arts, entertainment, and recreation (202); information (150), educational services (120), mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction (25); and utilities (7).

Models featuring reopening of non-essential businesses and restaurants dine-in services are available in the Supplementary Information file.

As multiple policies were enacted at similar times, one relevant question is whether the multiplicity of policy interventions affected businesses’ perceptions and attitudes. To explore this question, we replicated our models using the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker’s Stringency Index (Hale et al., 2021). The stringency index varies from 0 to 100 and captures the stringency of closure policies affecting each state based on the following policies: school closures, workplace closures, cancellation of public events, restrictions on gathering size, closures of public transportation, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on internal movements, and restrictions on internal travels. The results show that closure policies were associated with worse perceptions, reductions in employment in total and hourly, and lower self-employment recovery rates—therefore, confirming our conclusions. Results are available from the authors upon request.

References

An, B. Y., Porcher, S., Tang, S., & Kim, E. E. (2021). Policy design for COVID-19: Worldwide evidence on the efficacies of early mask mandates and other policy interventions. Public Administration Review, 81(6), 1157–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13426

Balla-Elliott, D., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2022). Determinants of small business reopening decisions after COVID restrictions were lifted. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 41(1), 278–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22355

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17656–17666. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006991117

Belghitar, Y., Moro, A., & Radić, N. (2022). When the rainy day is the worst hurricane ever: The effects of governmental policies on SMEs during COVID-19. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 943–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00510-8

Courtemanche, C., Garuccio, J., Le, A., Pinkston, J., & Yelowitz, A. (2020). Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Affairs, 39(7), 1237–1246. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608

Curley, C., & Federman, P. S. (2020). State executive orders: Nuance in restrictions, revealing suspensions, and decisions to enforce. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 623–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13250

Demko, I., & Sant’Anna, A. C. (2023). Impact of race, ethnicity, and gender on the SBA Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan amounts. Economic Development Quarterly, 37(3):211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912424231171847

Desai, S., & Looze, J. (2020). Business owner perceptions of COVID-19 effects on the business: Preliminary findings. Kauffman Foundation Research Brief: Trends in Entrepreneurship, No. 10. https://www.kauffman.org/entrepreneurship/reports/business-owner-perceptions-covid-19/

Ding, L., & Sánchez, A. (2020). What small businesses will be impacted by COVID-19? Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Research Brief.

Dua, A., Ellingrud, K., Mahajan, D., & Silberg, J. (2020). Which small businesses are most vulnerable to COVID-19 – and when. McKinsey & Company Featured Insights Article.

Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 29(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12400

Fairlie, R., & Fossen, F. M. (2022). Did the Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program get disbursed to minority communities in the early stages of COVID-19? Small Business Economics, 58(2), 829–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00501-9

Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., Warren, J. R., & Westberry, M. (2021). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 10.0 . In IPUMS. IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V9.0

Goolsbee, A., Luo, N. B., Nesbitt, R., & Syverson, C. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown policies at the state and local level. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3682144

Granja, J., Makridis, C., Yannelis, C., & Zwick, E. (2020). Did the Paycheck Protection Program hit the target? (27095). Journal of Financial Economics, 145(3):725–761. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27095

Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

Li, H., & Stoler, J. (2023). COVID-19 and urban futures: Impacts on business closures in Miami-Dade County. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 113(4), 834–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2134839

Light, A., & Mung, R. (2018). Business ownership versus self-employment. Industrial Relations. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12213

Lyu, W., & Wehby, G. L. (2020). Shelter-in-place orders reduced COVID-19 mortality and reduced the rate of growth in hospitalizations. Health Affairs, 39(9), 1615–1623. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00719

Marshall, M. I., & Schrank, H. L. (2014). Small business disaster recovery: A research framework. Natural Hazards, 72(2), 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-1025-z

Motoyama, Y. (2020). What kind of cities are more vulnerable during the COVID-19 crisis? Local Development & Society, 1(1), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/26883597.2020.1794755

Motoyama, Y. (2022). Is COVID-19 causing more business closures in poor and minority neighborhoods? Economic Development Quarterly, 36(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912424221086927

Ong, P., Comandon, A., DiRago, N., & Harper, L. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on minority businesses and systemic inequality. UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge.

Raifman J, Nocka K, Jones D, Bor J, Lipson S, Jay J, & Chan P. (2020). “COVID-19 US State Policy Database.” Available at: www.tinyurl.com/statepolicies.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Small Business Pulse Survey. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/small-business-pulse-survey.html

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2022). Forgiveness platform lender submission metrics as of October 23, 2022. Available at: https://www.sba.gov/sites/sbagov/files/2022-10/2022.10.24_Weekly%20Forgiveness%20Report_Public.pdf

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2021). Paycheck Protection Program report. Approvals Through 05/31/2021. Available at: https://www.sba.gov/sites/sbagov/files/2021-06/PPP_Report_Public_210531-508.pdf

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2020a). Paycheck Protection Program report. Approvals Through 08/08/2020. Available at: https://www.sba.gov/sites/sbagov/files/2021-09/PPP_Report%20-%202020-08-10-508.pdf

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2020b). Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) data.

USAFacts. (2020). US COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/state/georgia

Wang, Q., & Kang, W. (2021). What are the impacts of COVID-19 on small businesses in the U.S.? Early evidence based on the largest 50 MSAs. Geographical Review, 111(4), 528–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167428.2021.1927731

Warner, M. E., & Zhang, X. (2021). Social safety nets and COVID-19 stay home orders across US states: A comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(2), 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2021.1874243

Waugh, W. L., Jr., & Liu, C. Y. (2014). Disasters, the whole community, and development as capacity building. In N. Kapucu & K. T. Liou (Eds.), Disasters & Development: Examining Global Issues and Cases (1st ed., pp. 167–179). New York, NY: Springer.

Wilmoth, D. (2021). The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on small businesses. U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy Issue Brief Number 16.

Xiao, Y., Wu, K., Finn, D., & Chandrasekhar, D. (2022). Community Businesses as social units in post-disaster recovery. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18804328

Zhang, X., & Warner, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 policy differences across US states: Shutdowns, reopening, and mask mandates. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249520

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C.Y., Nazareno, L. State responses during the COVID-19 pandemic and their impacts on small businesses. Small Bus Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-024-00923-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-024-00923-1