Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of a professional development (PD) program on preschool teacher assistants’ (TAs) attitudes toward multilingualism and self-efficacy in working with linguistically and culturally diverse children (LCDC) and their parents. The study was conducted in a northern peripheral city in Israel that reflects the country’s multicultural, multilingual mosaic. Recently, as part of reforms in the city, PD for TAs was introduced to enrich the participants’ practical knowledge about the development and education of linguistically and culturally diverse children. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from 59 TAs before and after PD. Questionnaires focused on TAs’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms, as well as on their attitudes toward multilingualism. In addition, participants reflected on an event in their preschool with a child whose home language was other than Hebrew—the societally dominant language—focusing on the TAs’ emotional and behavioral responses. The qualitative and the quantitative data point to the impact of this PD program. Dependent variables t-test analysis revealed significant increase in TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC and with parents, thus supporting classroom multilingualism. Mixed-method analysis of the qualitative data showed a decrease in negative feelings such as anxiety, disappointment, low self-esteem, and unpreparedness for handling LCDC, and an increase in positive feelings such as happiness, pride, satisfaction, achievement, and self-efficacy. The discussion addresses three issues: the importance of multicultural, multilingual professional development for TAs, self-efficacy as a central characteristic of TAs’ functioning, and the importance of TAs’ relationships with parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study was conducted in the North of Israel in a small city characterized by a multilingual, multicultural population. Although this linguistic and cultural diversity enriches its peoplehood landscape, it poses challenges to the education system from early childhood to high school. Local education policymakers have recently initiated a program to support early childhood education linguistically and culturally diverse children (LCDC). To this end, all preschool teachers and staff participated in a professional development (PD) program that had the aim of improving their attitudes toward multilingualism and classroom support of home languages and to increase their self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their families. In this study, we evaluated and discussed outcomes of this PD, specifically regarding teacher assistants (TAs).

An extensive body of literature indicates that high-quality educators are essential for classroom quality in early childhood education and care (NICHD ECCRN, 2002). Teacher assistants (TAs) are caregivers who, for years, have been outside the focus of early childhood education policymakers and researchers. Today, however, in light of the vast waves of immigrants worldwide, TAs are often the first educational figures to encounter the immigrant children on their arrival. Once the target of implementing linguistically and culturally responsive teaching in classrooms (Hollie, 2019) has been set, these frequently neglected TAs play an important role in the practical application of the approach.

The present study has two main objectives: (1) to learn more about the attitudes and practices of TAs as an under-researched population of care givers and (2) to examine the effect of a brief PD program designed to equip TAs teaching in preschools with multiculturally diverse populations with knowledge and skills for working with preschool LCDC.

Literature Review

In this section, we address the following theoretical approaches most relevant to the study: Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Teaching (LCRT); the essential role of TAs in approaching LCDC and their families; support for multilingualism in classrooms; the importance of self-efficacy in working in multilingual classrooms, and the benefit of professional development (PD).

Teaching Assistants as an Under-Researched Population of Caregivers and their Self-efficacy in Working with LCDC

Self-efficacy, a central concept in social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), is viewed as the foundation of caregivers’ agency. Self-efficacy reflects a sense of “how good I am” at a given activity and my beliefs about “how well I can cope” with different situations in the future (Bandura, 1977). These beliefs affect our choices, task-specific effort investment, level of aspiration, commitment to goals, persistence in difficult situations, and resilience to stress (Bandura, 2012; Lauermann & Hagen, 2021).

Most studies have focused on teacher self-efficacy and its enhancements to school and preschool (Lauermann & Hagen, 2021). Studies on TAs in general, and more specifically on TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC are rare (Tse, 2021). Generally, preschool TAs are not formally educated or certified to work with children. They frequently suffer from lack of professional definition and development. At the same time, TAs carry out a wide range of roles in preschool (e.g., administrative, pedagogic, emotional, and social support of children) (Kerry, 2005). TAs are responsible for welcoming routines in the morning and closing the preschool, as well as cleaning, assisting the teacher to prepare teaching materials, and looking after the children in the yard (Oplatka & Eizenberg, 2007). In addition, they communicate with parents in the morning and at the end of the day (Drugli & Undheim, 2012). Furthermore, TAs are perceived as a critical factor in preschool teachers’ career development, especially for new teachers. TAs’ emotional support and positive feedback help teachers develop either self-evaluation and professional confidence or the opposite (Oplatka & Eizenberg, 2007). Given that TAs have consistent daily interaction with teachers, children, and parents, they are considered to be highly influential on the preschool atmosphere, the collaborating relationships with teachers, and the rapport with parents (Drugli & Undheim, 2012; Sharma & Salend, 2016).

Recently, due to preschool teachers’ workloads, the role of the TA has increased and includes caring for the children’s welfare, managing individual and group behaviors, and facilitating teaching and learning of LCDC who are novel learners of the socially dominant language and frequently need help in the negotiation of meaning (Kerry, 2005; Sharma & Salend, 2016). Hence, the significance of this study is in exploring the effect of a brief PD on TAs, specifically on their self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their families. In addition, by applying the mixed-method approach, we examined how a brief PD influenced TAs’ knowledge about linguistically culturally responsive teaching and its strategies and their ability to implement this pedagogical approach. Since almost no research exists to date on how TAs function when they implement this pedagogy and on their PD in this field, in the following sections, we will overview what is known about preschool teachers.

Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Teaching (LCRT)

Since teachers often draw on their own cultural biases, and not all teachers are equipped with efficacy to work with LCDC and their parents in multicultural and multilingual classroom (Castro, 2010), the linguistically culturally responsive teaching approach requires preparation of teachers for diversity, emphasizing the teacher’s sense of competence, self-efficacy, and strategies to work with this population (Grimberg & Gummer, 2013).

Linguistically culturally responsive teaching includes the development of multilingual awareness (García, 2008). As twenty-first century classrooms present multilingual mosaics of children throughout the world, García (2008) claims that PD programs for teachers need to take a multilingual turn and “put language difference at the center” (p. 393). Thus, teachers’ education must include pedagogical strategies for promoting linguistically culturally responsive teaching. One such strategy is the incorporation of children’s home languages and experiences into negotiation of new content understanding, utilizing visual tools such as pictures, photos, and videos of their home country to provide a more meaningful context for children as learners. Another strategy is drawing on multimodality by activating body enactment and movement together with visual and language modalities. This not only improves understanding and memorization of novel words in L2 and of learning material, but also facilitates their production (Lucas & Villegas, 2010; Tellier, 2008).

This pedagogical approach is necessary for all teachers who work with LCDC, not only for language teachers. García (2008) explains that to be an expert, the teacher requires knowledge of the “bilingual and multilingual contexts in which the children live, and of the social practices that produce certain discourses” (p. 389), how a child’s languages impact each other, and how to draw on his or her multilingualism. Thus, teachers’ knowledge of linguistically culturally responsive teaching strategies is necessary for their self-efficacy in multilingual classrooms.

Teacher’s Self-efficacy in Multicultural Classrooms

Teachers’ self-efficacy is a predictor of their teaching quality (Klassen & Tze, 2014). Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) suggested three factors of teachers’ self-efficacy: self-efficacy for classroom management, self-efficacy for instructional strategies, and self-efficacy for student engagement referring to teachers’ beliefs in their ability to motivate students and help them to believe in themselves. Teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms has recently become a fourth dimension of the teachers’ self-efficacy (Lauermann & Hagen, 2021). Siwatu (2007, 2011) argued that teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms indicates teachers’ beliefs in their ability to adopt and employ strategies associated with linguistically culturally responsive teaching (e.g., drawing on students’ diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, scaffolding their understanding of a novel language, encouraging students’ respect for diversity in teamwork, and fostering positive relationships with students and their parents).

Teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms was found to be reflected in a range of studies (e.g., Tandon et al., 2017). Thus, a recent study by Dražnik et al. (2022) showed that novice teachers in three European countries, Slovenia, Spain, and Finland, expressed anxieties and fears regarding their future teaching of LCDC. The teachers in all three contexts described feelings such as anxiety, low self-esteem, and unpreparedness in approaching LCDC, due to low level of competence in linguistically culturally responsive teaching strategies and insufficient professional preparation. These negative feelings inevitably raise concern about teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms and place LCDC at risk of becoming “avoided and/or ignored” (Tandon et al., 2017, p. 165). Classroom diversity exposes teachers and students to different perspectives and enriches learning opportunities (Banks, 2008). However, not all teachers have an equal sense of efficacy regarding the teaching of LCDC. Teachers often teach according to their own cultural biases and report lower levels of comfort and self-efficacy when interacting with culturally diverse students (Kumar & Lauermann, 2018). Teachers’ high self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms has contributed significantly to children’s engagement, motivation, and competence in learning (Nykiel-Herbert, 2010; Rodríguez et al., 2014). Those teachers also have positive attitudes toward multilingualism and support children’s cultural identity development and home languages (Milner & Howard, 2013; Thompson & Byrnes, 2011).

Another challenge for teachers working in a multilingual classroom is their interaction with parents from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Home and school are the two primary and most influential contexts for young children’s learning and development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Moreover, it is not only the unique influence of each context that impacts children’s learning and development, but also the nature and quality of interaction between parents, teachers, and children (Epstein, 2010).

Various demographic background factors, such as, socioeconomic status, parents’ education, and family structure, affect parents’ involvement. Beyond demographic factors, there are psychological factors such as parents’ motivational beliefs, parents’ personal life contexts, parents’ perceptions of invitations for involvement, or how welcoming the preschool staff is (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005). Likewise, teachers experience various challenges and difficulties in their relationships with parents, as for example, in conflicts, unexpected struggles, parents’ distrust, and unreasonable demands (Bang, et al., 2021). Partnerships between teachers and parents will be more fulfilling when both are able to collaborate from equal positions to attain the same aims (Epstein, 2018). Thus, it is even more complicated for teachers to maintain relationships with immigrant parents or parents who do not speak the main local language and who are neither familiar with nor identify with the local culture. Immigrant parents are not always familiar with preschool norms; they hesitate to ask for clarification or to voice their own opinions to the teacher and often try to avoid conflict (Norheim & Moser, 2020). Regarding teachers’ points of view, reports of preschool teachers from Iceland and Israel about their relationships with multicultural, multilingual parents underline diverse teachers’ behaviors; on one hand, teachers report aspiring to connect with parents, but on the other hand, they report having a hierarchical relationship with parents (Schwartz, 2022). The present study focused on TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents.

Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Multilingualism in Classrooms

Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge are central facets of teacher agency (Biesta et al., 2015; Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). In this paper, we adopt Johnson and Johnson’s definition of attitudes as they “may be thought of as opinions, beliefs, ways of responding, to some set of problems” (Johnson & Johnson, 1999; p. 14). The concept of language ideologies was suggested by Silverstein (1979), who described “linguistic ideologies” as how people think language functions and how it should be used. Language ideologies always present the interest of some social and cultural group, such as teachers (Spolsky, 2004).

Mainstream teachers’ language attitudes toward multilingualism in early childhood education and care may be expressed in their general assumption regarding multilingualism in the target society, the role of the socially dominant language in society versus immigrant languages (e.g., Bernstein et al., 2018; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, 2014; Kirsch & Aleksic, 2018), as well as specific thoughts regarding language use in their classroom and the role of children’s home language maintenance and enrichment (e.g., Kultti & Pramling, 2020; Mary & Young, 2018).

Recent quantitative surveys in North American and European contexts explored attitudes of teachers in early childhood education and care using a narrow, dichotomous approach: a monolingual and assimilation-oriented attitude toward the dominant language and culture versus a multilingual ideology that sees the presence of multiple languages as an economic and cultural asset (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, 2014). For example, in a recent study, Bernstein et al. (2018) examined language ideologies of 28 early childhood educators in Arizona. They analyzed preschool teachers’ language ideologies, as well as the relationships between ideologies and demographic and experiential variables. They found that, in general, teachers held multilingual ideologies and did not view multiple languages as a problem, although particular ideologies were significantly mediated by their educational level and their experience with studying languages.

A similar tendency was found in the European context. For example, Kirsch and Aleksić (2018) reported that based on the Luxembourg Ministry of Education, Children and Youth (2015), most early childhood education and care practitioners provide multilingual children with opportunities to express themselves in their home languages. However, some studies report controversial findings (e.g., Gkaintartzi et al., 2015). Thus, in the study by Gkaintartzi et al. (2015), which investigated attitudes of preschool and school teachers (822 participants) toward immigrant children’s L1 maintenance and bilingual development in Greece, almost half of the teachers believed that knowledge of immigrant children’s home language is a hindrance to learning Greek, the mainstream language.

Some considerable gaps in current research on how early childhood education and care teachers experience multilingualism in classrooms need to be addressed. First, to the best of our knowledge, the available research did not provide an in-depth treatment of teachers’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and responding to the children’s needs. Although in many studies, early childhood teachers reported holding pro-multilingual stances and supporting home language maintenance. Nonetheless, many practitioners do not know how to implement linguistically culturally responsive teaching as a pedagogical approach and how to communicate with linguistically and culturally diverse families, and therefore PD is needed (Kirsch & Aleksić, 2018).

Professional Development in Multicultural Education

Early childhood educators address cultural, educational, and social challenges (Urban, 2008). Due to their professional demands, PD plays an essential role in promoting teachers’ level of competence (Ukkonen-Mikkola & Fonsen, 2018). PD in early childhood education and care was found to be most effective when this process influenced teachers’ pedagogical awareness and reflectivity and helped them enact their agency as “actors of change” in education (Eurofound, 2015; Peeters & Vandenbroeck, 2011; Peleman et al., 2018). Another effect of early childhood education teachers’ PD is empowering them “to question taken-for-granted assumptions that underlie their practices” (Peleman et al., 2018, p. 16).

Regarding school context, research reveals that mainstream teachers’ PD in multicultural education plays a central role in equipping teachers with self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms, and, in turn, this self-efficacy promotes a positive school climate (Choi & Lee, 2020). However, it is important to stress that although LCDC is a rapidly growing population in early childhood education and care all over the world, only a few studies examined how PD may empower early childhood teachers to work with LCDC and their families (Kirsch & Aleksić, 2018; Kirsch et al., 2020). These very limited studies point to the positive effect of a brief PD program on teachers’ readiness to reconsider their erroneous views about language development in a multilingual environment and to become more open to using children’s home languages in mainstream early childhood education and care institutions.

To recap, drawing on this theoretical background, the aim of the present study was to increase understanding of the effect of PD on TAs as an under-researched professional population, on their attitudes toward multilingualism and home language support, and on their self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents.

The following research questions were asked:

-

1.

How and to what extent did PD influence TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism and home language support? Drawing on the theoretical background, we predicted that PD would positively affect TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism and home language support.

-

2.

How and to what extent did PD influence TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents? Since research on the impact of PD on teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms is scarce, we were cautious about predicting that TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents would increase following the professional development course.

Method

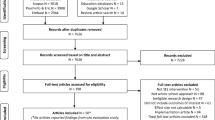

To address the research question, a concurrent mixed-method design, predominantly quantitative in nature, was employed in the study. We applied mixed-method methodology to achieve a broad picture, and to enhance the validity of our quantitative tools (e.g., Creswell & Clark, 2011), we included one open question in a closed-ended questionnaire.

Before describing the applied quantitative and qualitative methods in detail, we will provide a short overview of the PD program assessed in this study.

The Professional Development Program

This paper is based on data collected as part of a large-scale project named City Speaks Languages, which focuses on PD in early childhood education and care. The main goal of PD was to improve TAs’ interpersonal interactions with LCDC and their families and, as a result, to enhance children’s integration and to improve the preschool climate. Specifically, the aim of this PD was to increase TAs’ awareness of LCDC and their needs; to acquire perspectives on multilingual children’s social, linguistic, cognitive, and emotional development, to become familiar with linguistically culturally responsive teaching principles, and to help TAs develop activities while drawing on these principles. The PD program was conducted in a professional development center for teachers’ PD in the city by specialized coaches or pedagogical counsellors. These coaches were instructed by the research team, who are experienced early childhood education and care teacher trainers in one of the leading pedagogical colleges in Israel. This team has more than 15 years of collective experience in early language education research. The PD content drew on central theories of children’s early multilingual, multicultural development and language education, linguistically and culturally responsive teaching (e.g., Mary & Young, 2017), family funds of knowledge (e.g., Moll et al., 2006), and second language mediation strategies in early childhood education and care (Schwartz, 2022). In addition, focus was placed on interaction between TAs and parents from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Finally, the PD focused on enhancing TAs’ development of their personal and professional identity.

Eleven meetings (4 h each, 44 h overall) were held from July 2021 to September 2021. In general, the meetings encouraged TAs to discuss their beliefs about multilingualism on the macro state level and on the micro city level, to examine challenges they faced while working with LCDC and their families, and to reflect on language-supportive strategies. In addition, the goal was to promote TAs’ intercultural awareness as “the ability to communicate effectively in cross-cultural situations and to relate appropriately in a variety of cultural contexts” (Bennett & Bennett, 2004, p. 149).

After the introductory session, the first two meetings focused on professional and personal identity development in a multilingual, multicultural environment followed by three meetings dedicated to bi/multilingual children’s development and education in the early years. The next focus was language policy on four levels: state, community, classroom, and family, including characteristics of LCDC, their families, and communities in the city (three meetings). The last three meetings took the form of workshops aimed at developing specific strategies and activities, to enhance TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their families, such as, inter alia, creating bilingual/multilingual resources. All sessions took place in the city’s center for teachers’ PD.

It is noteworthy that all meetings were interactive and drew on “questioning taken-for-granted assumptions” as a ground for effective PD (Peleman et al., 2018, p. 16).

Participants

The final sample consisted of 59 TAs who completed questionnaires both pre- and post-PD. All participants were women, and their work experience ranged from 2 to 29 years. Participants were born in five different countries: 44% (n = 26) in Israel, 39% (n = 23) in Russia, 6.8% (n = 4) in Georgia, 5.1% (n = 3) in Morocco, and 3.4% (n = 2) in Ethiopia. Their ages at immigration ranged from 1 to 34 years. Most participants (72.9%, n = 43) had completed 12 years of school, and 11.9% (n = 7) held bachelor’s degrees. More than half (52.5%, n = 31) of the participants’ home language was Hebrew and all the rest spoke 11 different home languages (English, Arabic, Russian, French, Amharic, Spanish, Yiddish, Moroccan, Georgian, Romanian, and Polish). Only a few participants were monolingual (8.5%, n = 5) and the rest were either bilingual (52.5%, n = 31) or multilingual (39%, n = 23). Most participants (91.5%, n = 54) lived in the target city. Most participants were married (69.5%, n = 41), 22% (n = 13) were divorced, 6.8% (n = 4) were widowed, and one was single. All participants were mothers; the majority (50.8%, n = 30) had three children, 25.4% (n = 15) had two children, and 11.9% (n = 7) had four children.

Measures

To answer the research questions, we used a self-report survey consisting of three parts. The first part addressed background variables: work experience, education, marital status, number of children, home language, and number of spoken languages.

The second part comprises the following four sub-questionnaires:

Teacher assistants’ self- efficacy to work with preschool children (Friedman & Kass, 2000). The questionnaire included eight items with responses on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all; 5 = to a great extent); five items described high self-efficacy (e.g., “I am usually able to find effective ways to make a connection with the preschool children”) and three items referred to low self-efficacy and were reversed during data processing (e.g., “When a problem arises in preschool, I have difficulty solving it independently”). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.637 and at Time 2 was α = 0.715.

Culturally responsive self-efficacy (Choi & Lee, 2020). Teacher assistants were asked as follows: “When teaching a culturally diverse class, to what extent can you do the following?” The question referred to six items (e.g., “I can adapt my teaching to the cultural diversity of children”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.823, and at Time 2 was α = 0.834.

Self-efficacy to work with parents (Ames et al., 1995). Teacher assistants’ self-efficacy focused on parent involvement and included two items (e.g., “I have a lot of ideas about how to get parents interested in children’s learning”). Responses were on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). Reliability at Time 1 was r = 0.481** and at Time 2 was r = 0.668**.

Language ideology (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, 2011). TAs were asked to rate their perceptions regarding the use of languages. This questionnaire included 16 items with responses on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = definitely against, 6 = definitely agree). The items were modified and adapted to Israeli culture and to Hebrew, one of the official languages in Israel. The questionnaire included five factors: (1) Perceptions regarding monolingualism, two items (e.g., “The use of more than one language creates social problems”). Reliability at Time 1 was r = 0.437** and at Time 2 was r = 0.372**; (2) Perceptions regarding multilingualism, five items (e.g., “Speakers have the right to choose the language that they will use in any situation”). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.507 and at Time 2 was α = 0.522; (3) Hebrew language as a tool, three items (e.g., “In Israel, Hebrew is important for gaining material wealth”). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.711 and at Time 2 was α = 0.732; (4) “Speak Hebrew!” three items (e.g., “In Israel, public communication should occur in Hebrew”). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.611 and at Time 2 was α = 0.639; (5) Hebrew language as a national unifier, three items (e.g., “Knowing Hebrew helps in becoming Israeli”). Reliability at Time 1 was α = 0.679 and at Time 2 was α = 0.655.

The third part of the survey included an open question asking the participants to describe an event in their preschool with a child whose home language was other than Hebrew and to reflect on their emotional and behavioral reactions. These descriptions reflected on the participants’ self-efficacy in facing needs of LCRC and their families. This open question was analyzed based on both the qualitative and quantitative methodology that will be addressed later.

Procedure

TAs were asked to complete a survey prior to and after the PD course. We asked them to write a code (their mother’s first and last name initials and their date of birth), which helped us to merge between Time 1 and Time 2 later on. The research was approved by the Research and Evaluation Authority’s ethics committee at the authors’ academic institution and by the Chief Scientist at the Ministry of Education, as required in Israel. The researchers have experience in early childhood education and instruct courses in early childhood development and linguistically and multiculturally responsive teaching.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS Version 25. The analysis included descriptive statistical analysis to examine TAs’ levels of self-efficacy and language ideology, and a t-test analysis was calculated to examine differences pre- and post-PD.

The open question was analyzed by means of thematic analysis, which allows identification of people’s attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge (Caulfield, 2019). Based on the TAs’ reflections on a meaningful event related to their work with LCDC, we conducted thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), which included six steps: (1) Transcribing the interviews, (2) Studying the transcribed interviews and discussing the content with other researchers on the team, (3) Formulating patterns in the data set and building coding for these patterns, (4) Generating themes from the codes, (5) Assessment of the themes by an independent reader to improve the credibility of the analysis, and (6) Selecting the most illustrative excerpts.

Frequency of linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies expressed in TAs’ reflections prior to and after their PD course was counted. In addition, positive and negative emotions expressed by TAs were identified. Two independent judges counted the number of statements made in the TAs’ stories regarding their work with LCDC prior to and after PD.

We also calculated the frequency of reports on the sense of self-efficacy (i.e., positive, and negative statements regarding linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies) before and after the intervention, to achieve a more precise examination of self-reported changes in TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their families as a result of PD (Maxwell, 2010). The analysis of linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies, such as learning basic words in order to communicate with the child, was based on descriptions proposed by Ηοllie (2012), Lucas and Villegas (2010, 2013), and Bennett et al. (2017).

Results

The following two sections present the findings from the quantitative data (questionnaires with close-ended questions) and qualitative data (open question) in relation to preschool TAs’ changes in attitudes and practices in relation to LCDC and their parents.

Findings from the Quantitative Data

In response to the two hypotheses about differences between Time 1 (prior to the PD course) and Time 2 (after the PD course) regarding TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents and TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism and home language support, we conducted a comparative dependent t-test analysis between Time 1 and Time 2 of all research variables. The analysis revealed three differences between Time 1 and Time 2: TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents was significantly higher at Time 2. In addition, TAs’ perceptions regarding multilingualism were significantly more positive after the PD course (see Table 1, Time 2).

First, the results showed significant differences between the participants’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their parents before the course, at Time 1 (M = 3.23, SD = 0.34; M = 3.48, SD = 0.70) and after the course, at Time 2 (M = 3.52, SD = 0.52; M = 4.00, SD = 0.80), t(27) = − 3.03, p < 0.01; t(29) = − 3.77, p < 0.001. Second, and by contrast, there was no significant difference between TAs’ general self-efficacy to work in preschool, regardless of its population characteristics. This pattern of data may highlight the significant impact of the PD program described above that was aimed at promoting practitioners’ self-efficacy when addressing needs of LCDC and their families.

Regarding TAs’ language ideology, there were no differences between Time 1 and Time 2, on four out of five items related to participants’ beliefs. Thus, participants somewhat disagreed with pro-monolingual ideologies (M = 2.70, SD = 1.02). In addition, the majority of TAs positively endorsed items associated with perceptions regarding the role of Hebrew as a socially dominant language and as a tool for economic success at both periods of comparison, at Time 1 (M = 4.22, SD = 1.18) and at Time 2 (M = 4.58, SD = 1.55), and regarding the role of Hebrew as a national unifier at Time 1 (M = 4.04; SD = 1.27) and at Time 2 (M = 4.62, SD = 1.48), as well as regarding the necessity to communicate in this language in public spaces, at Time 1 (M = 3.66; SD = 1.24) and at Time 2 (M = 4.32, SD = 1.42). These attitudes can be attributed to the historical process of Hebrew revival. As the Judaic language of prayer and literature over many centuries, Hebrew began to be revitalized in the late nineteenth century. Through the efforts of many devoted and enthusiastic educators, who were committed to teaching the language and to its every-day use, Hebrew became an official language of the State of Israel (Spolsky & Shohamy, 1999). However, as predicted, following the PD program, the participants changed their attitudes and were more in favor of multilingualism. Analysis showed significant differences between Time 1, (M = 4.48, SD = 0.57) prior to PD, and after the course, at Time 2 (M = 5.06, SD = 0.39), t(16) = − 2.77, p < 0.01.

Findings from the Qualitative Data

In this section, we will present our analysis regarding TAs’ descriptions of an event in their preschool involving LCDC and their parents, in two parts: (1) Analysis of the frequency of the emotions expressed and reports on the sense of self-efficacy prior to and after the PD; (2) Thematic analysis of the TAs’ reports.

Frequency Analysis in TAs’ Reports

Our analysis of frequency of the emotions expressed revealed an increase in positive emotions and a decrease in negative emotions after PD, pointing to growing self-efficacy (see Table 2). Specifically, after PD, the participants more frequently expressed emotions such as self-confidence, satisfaction, and pride in being self-efficient in meeting LCDC’s needs.

Moreover, TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC, as expressed in the number of the reported linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies, increased after PD. It is noteworthy that the students’ parents and families were not mentioned at all at Time 1, prior to PD but, after PD, a considerable number of TAs mentioned the importance of working with LCDC’s parents and families. These findings support the quantitative research findings and indicate an improvement among TA following the PD program, both emotionally, in general, and in their self-efficacy to work with LCDC and their parents.

Thematic Analysis of TAs’ Reports

The thematic analysis of the TAs’ reflections on a meaningful event they remembered, related to working with LCDC, resulted in identifying the following themes that showed changes in TAs’ self-efficacy in working with LCDC and their families: (1) Reflective capacity; (2) Self-efficacy evaluation; (3) Agency enactment through diverse linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies when working with LCDC and their parents.

The identified themes were consistent with characteristics of human agency, in general (Bandura, 1977), and teacher agency, in particular (Priestley et al., 2015). Although the participants continued to report the challenges of working in a multilingual classroom, our analysis revealed that, after PD, TAs could provide more extensive and in-depth reflections on their capacity to address LCDC’s needs. These changes were reflected in their reports on intentional implementation of diverse linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies. The changes are illustrated in Table 3, by M’s reflection on events that had been meaningful for her, at Time 1 and at Time 2.

Evidently, the TA’s reflection showed the tendency to express solidarity with children and use of varied language strategies to negotiate their understanding of Hebrew (L2) and to help their absorption in preschool at both Time 1 and Time 2. However, only after PD, at Time 2, were the TAs more proactive and reported feeling solidarity with parents and how their self-efficacy had emerged in the multicultural classroom.

In general, we identified more cases of proactive behavior, such as the initiation of different affordances to make communication with families more efficient, as was stressed in the following description by S:

We have a child with an allergy in preschool. Information was sent but that family did not get the message because they did not understand the language. This put the allergic child in danger. I thought that we should have thought outside of the box, and we should have given information in other languages as well, or at least translated. We called the family and spoke to them in their language.

Thus, participation in the PD course apparently enhanced the TA’s ability to think “outside of the box.” In addition, in many cases, TAs’ reports of proactive behavior were accompanied by expressions of positive emotions, highlighting their satisfaction (“it was a pleasure to see [the child’s] progress [in Hebrew],”) and self-esteem (“a clever and inquisitive child … became attached to us also because of patience, attention, and understanding”).

More specifically, the analysis of participants’ reports showed that, after the intervention, TAs began to express solidarity with parents’ hardships and felt empathy toward them, as described by L:

The thoughts that came to my mind [referred to] the feeling of what it was like when I immigrated to Israel at age 4, how I felt, how my feelings were, how I coped, how I spoke and communicated when no one spoke my language. I tried to calm them down [the family] to give them a feeling of belonging [and assurance] that we will help with everything.

In addition, TAs reported more about drawing on language mediators (children, other parents who were competent in Hebrew, and community mediators) to communicate with families, to exchange information, and to negotiate understanding:

In our preschool, there are many new immigrants from Ukraine and Russia. Some of the parents do not know Hebrew and, therefore, it is hard for us to communicate with them. Neither I nor the preschool teacher know Russian; therefore, we sometimes make use of the preschool children and other children’s parents to translate for the child’s parents into Russian, their mother tongue.

These efforts seem to result in creating trustful relationships with the families since increasing trust may lead to the development of an environment that respects linguistic and cultural differences (Purnell et al., 2007).

We have a Russian speaking girl whose parents don’t speak a word of Hebrew and I communicated with her on WhatsApp via translators from Russian to Hebrew and she was so grateful and said that now she has no fear of sending the girl to preschool and she completely understands me and she is very calm when the girl goes to preschool.

In addition, TAs reported more cases of using a child’s home language to negotiate meanings in interaction with the child and his/her parents, as illustrated by M.:

I tried to learn basic words to communicate with the child, like bathroom, water, playground, a gathering [of children at the beginning and end of school day] and, slowly, the child learned and made friends. It was hard at first but, in the end, he learned everything like all the other children. He sang and danced, he worked nicely. We had a child of refugees from Syria who did not know Hebrew at all and neither did the family. When he came to us at the beginning of the year, we communicated with him, the preschool teacher and I, using basic words that we knew in Arabic. A clever and inquisitive child … he became attached to us also because of patience, attention and understanding.

Another linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategy was utilization of visual tools, such as pictures, photos, and videos, to provide a more meaningful context for children and improve their understanding of Hebrew.

Discussion and Implications for Practice

In this study, we examined the effect of PD on TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism, in general, and toward home-language support in classrooms, in particular, as well as if and how TAs could address the needs of LCDC and their families by implementing linguistically and culturally responsive teaching strategies. The findings suggest that experience in multicultural education, reflected in PD, played an important role in equipping TAs with LCDC in classrooms. The quantitative findings revealed that PD had a positive effect on TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC and their parents. In a similar vein, Choi and Lee (2020) found that PD in multicultural education improved teachers’ self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms. In addition, the findings of the present study indicated that TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism were more positive after PD. Likewise, Kirsch and Aleksic (2018) found a positive influence of PD on professionals’ knowledge about multilingualism and their attitudes toward home languages.

The qualitative findings confirm the quantitative findings and show that, after PD, TAs felt more confident to work with LCDC and were aware of the importance of parents; thus, they were willing to contact and to engage with LCDC’s parents. These findings point to three main issues: (1) the importance of TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC (2) the importance of TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC’s parents, and (3) the impact of PD on TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism.

In sum, the present study highlights the effect of PD on TAs, as a neglected and under-researched population in terms of educational investment. To the best of our knowledge, most studies in this area were conducted among early childhood teachers; very little is known about TAs’ self-efficacy to work with children and parents, and even less is known about TAs’ self-efficacy to work with LCDC and their parents. In the following sections, we will discuss the results in detail.

The Impact of PD on TAs’ Self-efficacy to Work with LCDC and Parents

Teacher–parent relationships are intertwined with wide-ranging social-cultural dynamics (Dusi, 2012). These relationships are affected by individual behaviors and attitudes, which are influenced by social and cultural orientation (Bang et al., 2021). Although it is well known that teacher–parent relationships have great value for children’s development and functioning, most preschool teachers and TAs do not receive training to work with parents, in general, and with parents from different cultures, in particular. Epstein (2013) noted that teachers need to know how to facilitate positive and respectful interactions with parents and to convey the message that they value parents’ input on their children’s education. However, not all preservice teachers, or teachers in general, naturally possess strong communication skills (Epstein, 2018). The development of effective communication skills requires a structured process and opportunities for practice (Kaplan Toren & Buchholz, 2019). In the present study, prior to PD, TAs’ self-efficacy to work with parents was lower than after PD, and in the qualitative analysis prior to PD, parents were not even mentioned.

Due to lack of training in this area, most of the teachers felt unprepared for effective engagement with families. According to teachers’ reports, parents ignored their requests, did not follow preschool norms, or had different expectations about teaching and learning. Thus, teachers often expressed negative attitudes toward parents, voiced concerns, and were reluctant to work with parents (Mahmood, 2013). The changes in TAs’ attitudes toward parents after PD, as reflected in our findings, strongly support TAs’ need for PD.

The Impact of PD on TAs’ Attitudes Toward Multilingualism and Multicultural Children

Multicultural education is essential for the development of the values of democracy and social justice, such as equity, justice, respect, and equality (Nieto, 2000). However, stereotypical perceptions and potential cultural bias are widespread even among educators (Kaplan Toren et al., 2018).

Studies have shown that interventions can affect stereotypical perceptions and potential cultural bias toward multiculturalism (Kumar et al., 2022). For example, Kumar and Hamer (2013) showed that preservice training can positively shape preservice teachers’ attitudes toward culturally diverse students and can encourage them to employ adaptive classroom practices. In the present study, changes were found in TAs’ attitudes toward multilingualism, but experience showed that to preserve this change, continued accompaniment and training are required (Kirsch & Aleksic, 2018).

In addition, the present research demonstrated positive changes in TAs’ emotions after PD. As Bandura (1989) suggested, people’s self-beliefs can affect their cognitive, affective, or motivational processes. Moreover, “a resilient sense of efficacy enhances socio-cognitive functioning in the relevant domain in many ways. People who have high assurance in their capabilities approach difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered rather than as threats to be avoided. Such an affirmative orientation fosters interest and increases involvement in activities. They set themselves challenging goals and maintain strong commitment to them” (Bandura, 1989, p. 731). In other words, people with high self-efficacy in the relevant domain are more likely to be active agents and to make things happen; their motivation contributes to their positive emotions. Thus, Waters and Sun (2016) found that parents who participated in strength-based intervention, when compared to a control group, showed higher self-efficacy (i.e., greater confidence and perceived ability to raise their children successfully) and positive emotions when thinking about their children. In the context of the current study, TAs’ PD helps them feel that their work in preschool is effective. By learning to identify a multicultural child’s needs and improving TA’s skills to work with multicultural children, TAs’ self-efficacy increased and their emotions in regard to working with multicultural children were more positive.

Conclusion

This study made several contributions to our understanding of PD designed for TAs. First, since this PD was shown to be essential, there is a need for TA training programs with the aim of preparing them for an effective relationship with LCDC and their parents. Researchers recommended that teacher-training programs be focused on asking questions at meetings with parents, paraphrasing, reflecting on content and feelings, holding summarizing and closing sessions, as well as using nonverbal communication (Symeou et al., 2012). Second, the training should be based on learning through experience focused not only on increasing teachers’ knowledge about the benefits of positive parent engagement, but also on providing teachers with opportunities to practice effective research-based strategies for engaging parents (Bachellier, 2015; Kaplan & Buchholz, 2019). Third, it appeared that even a brief PD followed by professional networking enhanced TAs’ agency enactment, as expressed in their reflections on challenging events in meeting the needs of LCDC.

Limitations

This study had two main limitations: One was the sample characteristics, as TAs in this study had relatively low levels of education, were from multilingual backgrounds, and had immigration experience. Most of the TAs were either bilingual or multilingual and therefore, the sample is not necessarily representative. Accordingly, future studies are recommended to examine TAs from a variety of populations that do not necessarily have multilingual backgrounds. The second limitation was that the PD was accompanied by other activities; that is, the TAs participated in a professional network meeting to discuss issues related to LCD classrooms. Therefore, the results of this study might be related also to TAs’ engagement in professional discussion groups.

References

Ames, C., de Stephano, L., Watkins, T., & Sheldon, S. (1995). Teachers’ school—To—home communications and parent involvement: The role of parent perceptions and beliefs. Paper presented at the AERA meeting, San Francisco.

Bachellier, T. E. (2015). Parent engagement pedagogy and practice in new preservice teacher education programs in Ontario. Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1719. http://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1719

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 729–735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44.

Bang, Y. S., Jang, H. J., & Jung, J. H. (2021). Understanding Korean early childhood teachers’ challenges in parent–teacher partnerships: Beyond individual matters. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(10), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10764

Banks, J. A. (2008). An introduction to multicultural education (4th ed.). Pearson.

Bennett, J. M., & Bennett, M. J. (2004). Developing intercultural sensitivity: An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp. 147–165). Sage Publications.

Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2017). The process of designing for learning: Understanding university teachers’ design work. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(1), 125–145.

Bernstein, K., Kilinc, S., Deeg, M., Marley, S., Farrand, K., & Kelley, M. F. (2018). Language ideologies of Arizona preschool teachers implementing dual language teaching for the first time: Pro-multilingual beliefs, practical concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(4), 457–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1476456

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34, 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

Castro, A. J. (2010). Themes in the research on preservice teachers’ views of cultural diversity: Implications for researching millennial preservice teachers. Education Researcher, 39(3), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X10363819

Caulfield, J. (2019). How to do thematic analysis. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/

Choi, S., & Lee, S. W. (2020). Enhancing teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms and school climate: The role of professional development in the multicultural education in the United State and South Korea. AERA Open, 4, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420973574

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. P. (2011). Mixed methods research. SAGE Publications.

Drugli, M. B., & Undheim, A. M. (2012). Partnership between parents and caregivers of young children in full-time daycare. Child Care in Practice, 18(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2011.621887

Dusi, P. (2012). The family-school relationships in Europe: A research review. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 2(1), 13–33.

Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023.

Epstein, J. (2010). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. Westview Pres.

Epstein, J. L. (2013). Ready or not? Preparing future educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Teaching Education, 24(2), 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2013.786887

Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. Routledge.

Eurofound. (2015). Working conditions, training of early childhood care workers and quality of services. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2011). Language ideology dimensions of politically active Arizona voters: An exploratory study. Language Awareness, 20(4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2011.598526

Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2014). Using lexical variables to identify language ideologies in a policy corpus. Corpora, 9(1), 57–82.

Freidman, I., & Kass, E. (2000). Teacher’s self-efficacy: The term and its measurement. Henrietta Szold Institute.

García, O. (2008). Multilingual language awareness and teacher education. In J. Cenoz & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Knowledge about language: Encyclopedia of language and education (2nd ed., Vol. 6, pp. 385–400). Springer.

Gkaintartzi, A., Kiliari, A., & Tsokalidou, R. (2015). ‘Invisible ’bilingualism–‘invisible “language ideologies: Greek teachers” attitudes towards immigrant pupils’ heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 18(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.877418

Grimberg, B. I., & Gummer, E. (2013). Teaching science from cultural points of intersection. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21066

Hollie, S. (2012). Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning: Classroom practices for student success. Shell Educational Publishing.

Hollie, S. (2019). Branding culturally relevant teaching. Teacher Education Quarterly, 46(4), 31–52.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1999). Making cooperative learning work. Theory Into Practice, 38(2), 67–73.

Kaplan Toren, N., & Buchholz, H. C. (2019). Preparing pre-service teachers to work with parents. Journal of School-Based Family Counseling, 11, 1–24.

Kaplan Toren, N., Schlesinger, R., & Musher-Eizenman, D. (2018). Prejudices among Arab and Jewish pre-service teachers about body image and appearance. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1472688

Kerry, T. (2005). Towards a typology for conceptualizing the roles of teaching assistants. Educational Review, 57(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910500149515

Kirsch, C., & Aleksic, G. (2018). The effect of professional development on multilingual education in early childhood in Luxembourg. Review of European Studies, 10, 148.

Kirsch, C., Aleksić, G., Mortini, S., & Andersen, K. (2020). Developing multilingual practices in early childhood education through professional development in Luxembourg. International Multilingual Research Journal, 14(4), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2020.1730023

Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76.

Kultti, A., & Pramling, N. (2020). Traditions of argumentation in teachers’ responses to multilingualism in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(3), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Kumar, R., Gray, D. L., & Toren, N. K. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ desire to control bias: Implications for the endorsement of culturally affirming classroom practices. Learning and Instruction, 78, 101512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101512

Kumar, R., & Hamer, L. (2013). Preservice teachers’ attitudes and beliefs toward student diversity and proposed instructional practices: A sequential design study. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487112466899

Kumar, R., & Lauermann, F. (2018). Cultural beliefs and instructional intentions: Do experiences in teacher education institutions matter? American Educational Research Journal, 55(3), 419–452.

Lauermann, F., & ten Hagen, I. (2021). Do teachers’ perceived teaching competence and self-efficacy affect students’ academic outcomes? A closer look at student-reported classroom processes and outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 56(4), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2021.1991355

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2010). The missing piece in teacher education: The preparation of linguistically responsive teachers. Teachers College Record, 112(14), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811011201402

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 52(2), 98–109.

Mahmood, S. (2013). First-year preschool and kindergarten teachers: Challenges of working with parents. School Community Journal, 23(2), 55–86.

Mary, L., & Young, A. (2017). Engaging with emergent bilinguals and their families in the pre-primary classroom to foster well-being, learning and inclusion. Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(4), 455–473.

Mary, L., & Young, A. (2018). Parents in the playground, headscarves in the school and an inspector taken hostage: Exercising agency and challenging dominant deficit discourses in a multilingual pre-school in France. Language, Culture & Curriculum, 31(3), 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2018.1504403

Maxwell, J. A. (2010). Using numbers in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 475–482.

Milner, H. R., IV., & Howard, T. C. (2013). Counter-narrative as method: Race, policy and research for teacher education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(4), 536–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.817772

Ministry of National Education, Childhood and Youth of Luxembourg and Integrative Research Unit on Social and Individual Development of the University of Luxembourg. (2015). D’Éducation précoce: Mat de Kanner, fird’Kanner! Bericht [Preschool education: With children, for children! Report]. http://www.men.public.lu/catalogue-publications/fondamental/statistiques-analyses/autres-themes/education-precoce/ed-prec.pdf

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (2006). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. In Funds of knowledge (pp. 71–87). Routledge.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). Child-care structure – process –outcome: Direct and indirect effects of child-care quality on young children’s development. Psychological Science, 13, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00438

Nieto, S. (2000). Placing equity front and center: Some thoughts on transforming teacher education for a new century. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003004

Norheim, H., & Moser, T. (2020). Barriers and facilitators for partnerships between parents with immigrant backgrounds and professionals in ECEC: A review based on empirical research. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(6), 789–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1836582

Nykiel-Herbert, B. (2010). Iraqi refugee students: From a collection of aliens to a community of learners–the role of cultural factors in the acquisition of literacy by Iraqi refugee students with interrupted formal education. Multicultural Education, 17(3), 2–14.

Oplatka, I., & Eizenberg, M. (2007). The perceived significance of the supervisor, the assistant, and parents for career development of beginning preschool teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.012

Peeters, J., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2011). Childcare practitioners and the process of professionalization. In Professionalization, leadership and management in the early years (Vol. 3, pp. 62–76). Sage

Peleman, B., Lazzari, A., Budginaitė, I., Siarova, H., Hauari, H., Peeters, J., & Cameron, C. (2018). Continuous professional development and ECEC quality: Findings from a European systematic literature review. European Journal of Education, 53(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12257

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: What is it and why does it matter? (pp. 134–148). Routledge.

Purnell, P. G., Ali, P., Begum, N., & Carter, M. (2007). Windows, bridges and mirrors: Building culturally responsive early childhood classrooms through the integration of literacy and the arts. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-007-0159-6

Rodríguez, S., Regueiro, B., Blas, R., Valle, A., Piñeiro, I., & Cerezo, R. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and its relationship with students’ affective and motivational variables in higher education. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 7(2), 107–120.

Schwartz, M. (2022). Language-conducive strategies in early language education: A conceptual framework. In M. Schwartz (Ed.), Handbook of early language education (pp. 1–26). Series Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. J. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(8), 118–134.

Silverstein, M. (1979). Language structure and linguistic ideology. In R. Clyne, W. Hanks, & C. Hofbauer (Eds.), The elentents: A parasession on linguistic units and levels (pp. 193–247). Chicago Linguistic Society.

Siwatu, K. O. (2007). Preservice teachers’ culturally responsive teaching self-efficacy and outcome expectancy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(7), 1086–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.07.011

Siwatu, K. O. (2011). Preservice teachers’ culturally responsive teaching self-efficacy-forming experiences: A mixed methods study. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(5), 360–369.

Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press.

Spolsky, B., & Shohamy, E. (1999). The languages of Israel: Policy, ideology and practice. Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Symeou, L., Roussounidou, E., & Michaelides, M. (2012). “I feel much more confident now to talk with parents”: An evaluation of in-service training on teacher-parent communication. School Community Journal, 22(1), 65–87.

Tandon, M., Viesca, K. M., Hueston, C., & Milbourn, T. (2017). Perceptions of linguistically responsive teaching in teacher candidates/novice teachers. Bilingual Research Journal, 40(2), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2017.1304464

Tellier, M. (2008). The effect of gestures on second language memorisation by young children. Gesture, 8(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.8.2.06tel

Thompson, J., & Byrnes, D. (2011). A more diverse circle of friends. Multicultural Perspectives, 13(2), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2011.571552

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tse, S. K., Pang, E. Y., To, H., Tsui, P. F., & Lam, L. S. (2021). Professional capacity building of multicultural teaching assistants in Hong Kong kindergartens with ethnic minority children. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 12(2), 234–244.

Ukkonen-Mikkola, T., & Fonsén, E. (2018). Researching Finnish Early Childhood Teachers’ pedagogical work using Layder’s research map. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(4), 48–56.

Urban, M. (2008). Dealing with uncertainty: Challenges and possibilities for the early childhood profession. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 16(2), 135–152.

Waters, L., & Sun, J. (2016). Can a brief strength-based parenting intervention boost self-efficacy and positive emotions in parents? International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-017-0007-x

Funding

Open access funding provided by Oranim Academic College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaplan Toren, N., Schwartz, M. Professional Development of Preschool Teacher Assistants in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts. Early Childhood Educ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01629-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01629-5