Abstract

The purpose of the study was to explore the sociodramatic play taking place in an early childhood classroom, with a specific focus on the characteristics of play, the game construction process that takes place during play, children’s agency in their play culture, and finally, the role of teachers as adults and as participants serving as guides and facilitators in the play. The study utilized an ethnographic case study approach to uncover play culture within the Little Daisies classroom. The data for the study came from lengthy observations throughout one school year in the classroom of 5-year-old children and semi-structured interviews with children regarding their sociodramatic play. Findings suggest that children constructing “games with rules” is a significant component of the classroom play culture, and non-distracted sociodramatic play provides children with many opportunities to practice their agency and function as social actors in their close environment. The concept of agency, teachers’ beliefs, and executive function skills were used to contextualize sociodramatic play for further discussion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“Hey, teacher! It is very nice to be a child, to play. If I were an adult, I could not have enjoyed it this much!” (Tuna, five years old)

Beyond any doubt, for those working in early childhood education, there is no “typical classroom” nor a typical game or form of play. Each early childhood classroom is unique, and so is children’s sociodramatic play, starting very early in their lives. Although children as young as nine months of age display initial socio-dramatic play behaviors (Deunk et al., 2008), socio-dramatic play in which children negotiate their roles, rules, and criteria is observed more distinctly starting about the age of three and continues to become more sophisticated throughout the early years (Smith & Pellegrini, 2008). As children develop and their play becomes more complex, they gradually start functioning as competent agents in a sociodramatic play context. Through sociodramatic play, children establish roles, build their stories, pursue a dialogue, and operate on connecting between different roles (Dinham & Chalk, 2018). Of course, as children develop, their cognitive functioning and accelerated language acquisition promote their interactions and relations with others as developmental notions enable children to organize information to reproduce their social worlds.

Various perspectives (Parten, 1932; Smilansky, 1968; Lester & Russel, 2008; Hughes & Melville, 2002) describe different types of play in the early years. Even though among all, Hughes and Melville (2002) offer the most detailed account of play with sixteen categories, this article used Smilansky’s perspective as it is the only one suggesting the category, games with rules. Within this type of play, children need to control themselves, their words, and their moves to follow the rules they create, although they still play within its generally accepted frame of reference. This naturally took place in the Little Daisies Classroom and is within the scope of this study.

The present study was an ethnographic case study intended to uncover play culture within the Little Daisies classroom, which was located on a university campus and designed to serve the university’s academic and administrative employees. While sociodramatic play and its significance in children’s development has been studied extensively in research, our purpose in this study was to uncover its role and vitality in the unfolding and development of children’s agency and to explore the link among socio-dramatic play, children’s play culture, game construction, and children’s agency. Therefore, the guiding research questions of the study were: (1) What is unique about the play culture in this classroom? (2) How does game construction occur during play and in the peer culture? (3) How can sociodramatic play support young children's emergence and advancement of agency? Throughout the study, children’s voice, and hence their agency, were captured to present children’s unique play culture and how it includes elements such as media, society, and institutions. While many studies focusing on children’s construction of their own culture have discussed peer culture, there still seems to be a vast need for studies explicitly addressing children’s play culture (e.g., Edwards, 2000; Kalliala, 2005; Lindqvist, 2001; Thyssen, 2003) that emerge out of children’s peer culture.

Theoretical and Conceptual Underpinnings

Corsaro’s Interpretive Reproduction Theory and Peer Culture

Corsaro’s (1992) groundbreaking theory and emphasis on the significance of peer interaction on child development contributed significantly to the notion of play culture. Corsaro proposed that simply through living with adults and having relationships with them, children get information about their social world and the world where adults are the ones generally perceived as the active agents, recreate this information via their thinking and create their own unique peer culture (Corsaro, 1992; Corsaro & Eder, 1990). Children’s peer culture is a joint product of adult and child cultures and is a result of the dynamic interaction between these two cultures (Corsaro, 2015). These two cultures are complicatedly interwoven, as opposed to having a linear relationship; Corsaro defined this construction process as “interpretive reproduction” (1992). By being in this shared production process, children’s childhoods are influenced by the cultures in which they live. As Corsaro states (1997, p.95), children’s peer culture constitutes different kinds of “stable set[s] of routines, values, artifacts, and concerns that they produce and share in interaction with peers.” Driven by Corsaro’s interpretive reproduction theory and children’s active construction of peer culture, the lenses of the present research focus on children’s play culture, which can be considered a subculture in the peer culture phenomenon.

Sociodramatic Play, Agency, and the Role of Cognitive Maturation

Beyond dispute, children have agency and can shape and alter their social worlds (Abebe, 2019). Abebe (2019) argues that the current understanding surrounding children’s agency is threefold. First, children have the biological preparedness to become agents in their earliest years; their agency develops as they mature and develop their cognitive skills and thinking. Second, a supportive environment, experiences, and the limitations employed upon children’s free will and behaviors allow children to display competence in structuring oppositional or productive relations with others and help them actualize their competence within the dynamic cultural relationship with others. Finally, another dimension of the current understanding of agency is that it is universal for all children and that children are capable and autonomous participants in society. When given the opportunity and right to participate, they can make decisions and behave in their best interest (Abebe, 2019). It is then reasonable to infer that sociodramatic play provides children with immense opportunities to “be,” to “do,” and to “produce” within a cultural setting, allowing for self-agency to be practiced and to develop.

New Sociology of Childhood and Children as Social Agents

Besides its role in children’s construction of knowledge, sociodramatic play serves as a medium through which children actively create their culture by producing new knowledge from their prior knowledge (Karabon, 2016). As the “new” sociology of childhood paradigm argues, children are social actors and, as a whole, human beings are “worthy of study in their own right, not as receptacles of adult teaching” (Hardman, 1973, p. 87). Moreover, it brought along the concept of children’s agency, which refers to children as social actors in their own lives and individuals who can make decisions about their lives (James & Prout, 1997). Therefore, using this perspective and focusing on children’s play allows for a thorough cultural evaluation of children's intentions and motives as social actors (James et al., 1998).

Goldman (1998) identified two distinct perspectives on play culture. First, children’s analysis of cultural identity and the social activities surrounding them. Second, their knowledge and understanding of play and how it can be carried out. Children are integral to society, so they experience the environment and social issues, learn the standard codes, and share meanings. Hence, children's play culture is essential to society’s general culture (Kalliala, 2005).

Danbolt and Enerstvedt (1995) describe play culture as “shared experiences, knowledge, ways of thinking, and language.” Play culture takes two forms. The first is “Culture for Children,” which includes play shaped by traditional and modern media such as books, cartoons, movies, and computer games. The second is the “Culture of Children,” created by children and developed through their jokes, abilities, and opinions.

Our research utilizes the new sociology of childhood in two ways. First, it attempts to examine how children create their games through sociodramatic play within the peer culture that shows the interaction between the culture of children and the culture for children. Children use constructs in society to create play products, which we refer to as games in this study. Second, the present study accepts children as social actors and active agents who can construct and sustain a unique culture. It aims to understand the intricacies involved in the construction process.

Methods

Design of the Study and Research Team

Our goal was to understand children’s play culture by analyzing their behavior. We chose a qualitative approach, specifically ethnography, to observe children spending extended time with their peers in a classroom environment. This allowed us to capture their experiences and play behaviors within their classroom community. We presented participants’ words and our explanation of a comprehensive design to create more meaning in children’s culture. We also utilized case study methods using several data collection methods.

The position of the first author, as the classroom teacher and her natural presence in the classroom as a part of the social group, made it easier for us to understand the culture, values, behaviors, and attitudes in the classroom. Furthermore, it made the ethnography possible. As the primary researcher (PR), the first author was also the head teacher of the classroom and had the opportunity to spend five days a week, from 08:30 to 17:00, with the children in the classroom. This provided us with a better understanding of the antecedents and consequences of the children's behavior, allowed us to discover patterns in their play, and helped us understand their relationships.

The primary researcher had worked as a teacher in this school for 5 years. She holds a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and is pursuing a graduate degree at the university where the Preschool Center is located. During this time, she had the opportunity to observe children’s play behaviors from different age groups. As the primary researcher, she conducted semi-structured interviews, collected children’s pictures, and observed self-initiated play to understand the children's play culture. Additionally, she observed different types of children’s play while serving as a student–teacher and head teacher. The second author is also a professional in early childhood education and served as the graduate advisor, providing guidance and supervision throughout the research. In terms of the study, the second author was primarily involved in coding and forming categories for data analysis, interpretation, and writing processes. The third author is a professional in child development and contributed to the interpretation and writing processes.

The Case: Little Daisies Classroom

In Turkey, early childhood education programs are available, but not mandatory, for children between birth and 72 months. In 2012, the Law About Adjustment to Elementary Education and Education Laws (numbered 6287) was passed. This law declared that children as young as 69 months of age have reached the compulsory education age and can attend elementary school (Tuğrul, 2018). As a result, in 2012, all children who were 68 months old were automatically registered for 1st grade, regardless of their readiness or parents' preference. However, in 2013, there was a change in the law, and readiness and parental choice became primary conditions for children to be registered for elementary education.

Early childhood education and care programs are available for young children in Turkey. Those serving children from birth to 24 months are supervised by the Ministry of Family and Labor and Social Services, including creches and daycares. Those serving children from 36 months to 69/72 months, including public preschools (with independent buildings), public kindergartens (attached to elementary schools), and private preschools, are supervised by The Ministry of National Education. Additionally, there are university-affiliated laboratory schools.

The Preschool Education Center, the setting for the study, was a university-affiliated laboratory school established in 1974. Since then, the center has served children from 1 to 6 years of age. This center’s primary mission is to contribute to children’s cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development while supporting children to be independent members of society by offering an enriching environment that allows them to build positive relationships with peers and adults. The center also focuses on helping children develop problem-solving and decision-making abilities and prepares them for primary education. The center offers an enriching environment with the aim of supporting children’s cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development, while also supporting their abilities to build positive relationships. The center utilizes the HighScope Approach (Schweinhart& Weikart, 1981), which requires the active involvement of both the teachers and the children.

The HighScope Educational Research Foundation is a non-profit organization that sponsors and supports the HighScope Educational Approach (Schweinhart& Weikart, 1981). This innovative program is based on Piaget's cognitive theory and aims to provide children with broad, realistic educational experiences. The approach emphasizes children’s active participation in choosing, organizing, and evaluating learning activities. Teachers carefully observe and guide children in a learning environment that includes a wide variety of materials in various classroom learning centers, and daily planning is done by the teaching staff, using a developmentally-based curriculum model. The approach also includes careful child observations and developmentally sequenced goals and materials based on HighScope key experiences.

In a typical HighScope classroom, adhering to the daily routine provides children with the consistency they need to develop a sense of responsibility while enjoying opportunities for independence. The routine includes planning time, essential experiences, work time, cleanup time, recall time, small group time, and large group time. Work time is generally the most extended single period in the daily routine, during which children execute their plans of work, and adults observe them to see how they gather information, interact with peers, solve problems, and enter into their activities to encourage, extend, and set up problem-solving situations whenever possible.

The center focuses on helping children to develop their problem-solving and decision-making abilities and prepares them for primary education. In line with the HighScope Approach, at least one-hour of self-directed work time is a vital part of the daily schedule, as it lets children play uninterruptedly and concentrate on their constructive processes. As seen in Table 1, the classroom hosting the study was comprised of ten children; five girls and five boys between 4 and 5 years old. Their ages varied by 11 months at most. Every day, the children were able to decide what they would play and with whom, and would initiate play at their own pace.

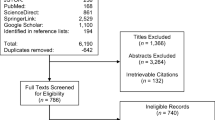

The research was implemented in this particular university preschool education center for several reasons. First of all, children have an unstructured and self-selected play time in which they can initiate their play freely for at least 1 h each day, from 10:00 to 11:00. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the sample schedule of the classroom, the center predominantly applies HighScope Approach (Schweinhart & Weikart, 1988), and even in the afternoons children have the opportunity for self-initiated play before leaving the school. Every day, children are able to decide what they will play, plan their games, and execute them for at least one hour of uninterrupted playtime.

Most of the children had been students in the school for four (4) years, having been there since they were two. Two of them joined the Little Daisies Classroom two years before the others. Children knew each other well and were accustomed to the school and the classroom environment, the garden daily schedule, and the school culture. Everybody knew each other by name, including all the teachers, school personnel, and the school manager. Hence, the school has a positive, friendly, and supportive atmosphere, and the children seem to have a strong sense of belongingness.

Data Collection

Data collection in ethnographic research involves specific steps, as Creswell (1998) described. Ethnographic research is conducted with the members of a culture-sharing group or individuals through participant observations, interviews, artifacts, and documents. The data is recorded through field notes, interviews, and observation protocols. The aim of ethnographic research is to make sense of and describe the culture within a specific culture-sharing group by gaining access through gatekeepers and gaining informants' confidence.

This study is performed through participant observations of children’s play, semi-structured interviews about their perceptions, field notes, and document analyses. The PR’s position as the head teacher of the classroom for 3 years and her warm, trusting, and affectionate relationship with class members were advantages in terms of access and rapport issues. As an early childhood education teacher during this time, she has participated in the children's play and asked them questions about the reasons and motives behind their choices and behaviors. So, it is believed that the present study and data collection tools did not create any role conflicts, did not influence or alter children's behaviors, and, more importantly, did not change the physical, social, and cultural environment. Aside from participant observations and field notes, semi-structured interviews were applied to gather children’s perceptions about their play descriptions. Through use of the interview questions, the researchers aimed to understand: (1) Descriptions regarding the children's play, (2) The reasons behind choosing this type of play, and (3) Behaviors according to the phases of play (i.e., planning phase, play phase, and end of play phase).

Data Collection Procedures

Before starting the study, the PR explained the research to the children, asked them whether they would like to share their experiences about sociodramatic play with PR, and received their assent. Since the PR is the head teacher and researcher in the 10-year-old classroom, data collection required extra planning. Observations, keeping field notes, and conducting semi-structured interviews generally took place during plan, do (work), and review times of the daily schedule.

In planning, children decide what to play, with whom to play, and where to play. To make their plans, children sat in a circle and explained their plans for their play. As mentioned earlier, there is at least 1 h of work time every morning, generally used for sociodramatic play by the children of the Little Daisies Classroom. When they were younger, they used brief sentences to explain their plans, such as, “I will play with dolls, I will play with blocks.” Sometimes, in their plans, they addressed their choice of a playmate with by saying, “I will play with Filiz; we will decide together what we will do” or “I will join in Can’s play.” As the children became older, they were better able to elaborate on their plans and provide specific details about their play plans. PR’s role as the researcher during this phase was to listen to the children’s ideas and decisions and to take notes. As children were used to PR’s note-taking behavior in class as a teacher and during the planning time, the note-taking as a researcher did not influence their behaviors or change the classroom atmosphere.

In the do phase, children initiate and continue playing. During this phase, they set the rules of play and decide the procedures. Sometimes, they may even rearrange the rules while continuing their play. As the researcher, PR either made observations and took notes or participated in the play when given the opportunity or asked to join. The PR also videotaped children’s play for later analyses. At all times, PR tried to follow the rules of the play and acted as a classroom member, not as the teacher with authority during the play. Keeping a reflective journal as a researcher helped PR immensely in this phase.

The review phase was when children ended playing games; the related data collection was aimed at understanding the reasons behind giving up playing games.

Data Analysis

As “ethnography involves prolonged observations of the group, typically through participant observation in which the researcher is immersed in the day-to-day lives of the people” (Creswell, 1998, p. 58), studying the meanings of behaviors, language, and interactions among the group members was necessary. The researchers described the events and setting without incorporating footnotes and intrusive analysis (Creswell, 2013; Wolcott, 1994). Verbatim audio and video recording transcriptions were performed, and the field notes were organized before data analysis. At the same time, the audio and video recordings were listened to and watched repeatedly to reach a complete understanding of the events in the setting. The descriptions were organized and re-read until the researchers developed familiarity and were fully immersed in the data. Searching for the patterned regularities in the data, we tried to draw connections between the children’s play behaviors and larger theoretical frameworks. During the analyses, some opinions, thoughts, and expressions are raised (Wolcott, 1994). As culture is “amorphous and not something “lying about” in Wolcott’s terms (1987, 41), the researchers have to make attributions by looking at the patterns of daily living. Looking for behaviors, language, and artifacts is a critical component in developing an understanding of the culture of a group (Spradley, 1980).

Coding and Formed Categories

Open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2007) was used to conceptualize, i.e., abstract the data as the data is broken down into discrete incidents, ideas, and events. Then, the researchers provided a name to each to ensure that the code was representative of the incidents, events, and ideas before engaging in comparative analysis to search for other events, ideas, and incidents that would be placed under the same code. After the descriptions were read repeatedly to reach an understanding, the events, behaviors, and conversations among children were named, which would lead to codes, following a search of the codes in different types of play scenarios and the construction processes of the play scenarios. Following the early coding process, comparative analysis was performed to discern the range of potential meanings and began to write memos, defined as records of analysis, thoughts, interpretations, questions, and directions for further data collection (Corbin & Strauss, 2007). Eventually, when we saw that the early codes that had formed could be applied to a majority of the play scenarios and the processes involved in the construction of play in the classroom, we began to form the categories, properties, dimensions and subcategories (Corbin & Strauss, 2007) (how children construct their play, who gets to play, how the play terminate etc. for play culture) to describe each type of play and the play culture in general.

Ethical Considerations

Before beginning of data collection, the PR applied to the Human Research Ethical Commission. Once approval was received, forms were given to families of the participating children to see whether they consented to their children’s participation in the study. Finally, the participating children’s verbal assent was obtained for the study. To construct the trustworthiness of the research, during the study process, the PR took some notes about the data and consulted with the second author to consolidate meanings, codes, and themes regularly. The PR ensured subjectivity and reflexivity issues by taking notes of her feelings and thoughts.

Results

The research questions of the present study were as follows: (1) What is unique about the play culture in this classroom? (2) How does game construction occur during play and in the peer culture? (3) How can sociodramatic play support young children's emergence and advancement of agency? Therefore, we will discuss the findings under the following themes: a general overview of play in the Little Daisies Classroom, general characteristics of play culture in the classroom, the game construction process in the classroom, and the teacher’s role in the construction process of games and in empowering children’s agency.

A General Overview of Play Culture in the Little Daisies Classroom

Children in the classroom generally prefered to engage in sociodramatic play. During planning, while children were gathered for circle time, they had opportunities to choose what to play, where to play, and with whom to play and carry out their plans for at least one hour of free play time, also called work time in the HighScope Curriculum model. In the HighScope model, group play consisting of two or more children is highly valued as it has been accepted as a significant path to individual development and classroom community building (Schweinhart & Weikart, 1988). Furthermore, teachers encourage children to play together when they ask questions during planning time, such as “Where do you want to play?" "What do you want to play?" and "With whom do you want to play?” This shared understanding allows children to develop a natural preference to play in groups. Meanwhile, as the children’s preferences and self-initiated play are the main drives guiding play, individual play is equally appreciated and valued. Therefore, one of the mediators for the socio-dramatic play is the teacher’s emphasis and encouragement. It is important to note that the small size of the classroom with only (10) children, also serves as a facilitator for group play.

Through sociodramatic play, children construct their own unique culture, rituals, and routines in the classroom. Other than sociodramatic play, there are also opportunities for children to engage in individual play, such as playing with cars, play dough, blocks, etc. However, individual play is not within the scope of this study, so the data for this type of play was not collected.

The children’s 1-hour uninterrupted play time starts at 10.00 a.m. and lasts until 11.00 a.m. However, children can initiate and engage in sociodramatic play anytime they find the opportunity outside of this scheduled uninterrupted playtime.

The play time, and hence their play, was under the control of the children, and they were conscious and serious about it. The PR introduced the study to the children and said that if they participated, they would play detectives to help them in their search for understanding their play. Once they agreed to participate, they kept inviting their teacher, saying, "Teacher, record this as well; we are playing this game.” They continued by sharing information such as, “Osman constructed this game.” One day, Beril said, “Teacher, let us show you how they play, and then she added: “and the applause is for them,” as if they were performing actors on stage.

Another day, Filiz told the PR that they were not playing because Yaman prevented them from playing their game. When Yaman was pretending to fight them with his pretend sword in his hand, Filiz started to chase him. While she was running after him with her sword in hand, she turned to the PR and said, “This is not a game, right now I am very mad.”

In addition to their awareness about their control over their play, they were also aware that they “built” the games, took pride in them, and said that until they left the school, the games would continue to exist. As they chose what to play and with whom to play, it was common to see that good friends generally took part in the same team, and they sometimes expressed it by saying, “Because we are gonna get married, we are in the same team.”

There were conventions of culture, which were commonly created, accepted, and shared by all the children in the classroom. For instance, they all knew that they had to wait for the child to start the game as he or she was the one who built it. “Built the game” was the common phrase they used while referring to the child’s act of construction and initiation. One child told the PR that he built it that day, was starting it, and would end it in the evening. The children all had games of their own and waited for each other to initiate the game, as shown by statements such as, “We cannot start this game yet; Filiz is not here,” or “Osman knows how to build these tents; we do not know.” Other conventions of play culture include rules such as not making weird noises, no spitting, not interrupting the flow of the game, etc.

Game Construction as an Artefact of the Play Culture of the Classroom

The game construction process beaome a vital ingredient of play culture in the Little Daisies Classroom. The categories that arose from data were as follows: how they created their play, how they decided who would play, how they dismissed players, how they terminated their play, and how this play evolved into other types of play.

Games of the Classroom

There are five main sociodramatic play scenarios that the children of the Little Daisies Classroom constructed and like to play during play times including the following: Naughty Baby-ing Game (Yaramaz Çocukçuluk), Scooby Doo-ing Game (Scooby Dooculuk), Cave-ing Game (Mağaracılık), Baby-ing Game (Bebekçilik), and Gun-ing Game (Silahçılık). These play scenarios are called games because each has specific characteristics and rules. Moreover, all the games are subject to specific criteria and structures born out of shared understanding and are joint products of the play culture of the classroom. These were not open to negotiation, and anyone who wanted to play was expected to respect this shared understanding within the group, as will be discussed in the following sections.

These games were constructed during the very early days of the 2015–2016 academic year. Although some of the games were based on cartoons or stemmed from the children's previous experiences, all were uniquely invented by the members of the Little Daisies Classroom.

Naughty Baby-ing Game

The Naughty Baby-ing game was initially set up by two children in which one pretends to be the baby, and the other pretends to be the caregiver, particularly the nanny or mommy. This narrative play includes daily issues and challenges between a baby and the mother in the home environment. For example, while the mother was busy in the kitchen, the baby got off his bed even though the mother told him not to do so, or the baby was engaging in a “naughty” activity, defined by the mother, which was in general related to sleeping or taking a nap.

Scooby Doo-ing Game

Scooby Doo is a cartoon widely popular among children in the classroom. Children created a new adventure each time they play this game, mostly about monsters coming from different places to attack the team. The team aims to destroy the monsters by creating new strategies such as finding a hiding place, running, and bringing some materials to fight against the monster.

Cave-ing Game

One specific child invented caving play, in which the children pretend to be adventurers in the game. They try to enter a dark and narrow cave to find the golden bucket. There is a play leader, the founder of the cave-ing game, and he leads the others in their search for the gold bucket.

Baby-ing Game

This is a game in which children pretend to be a family. There is a dad, a mom, one or two babies depending on the number of children who want to play, and a family pet, primarily cats and dogs and occasionally parrots. The episodes include family daily life activities such as going on a holiday, airplane boarding, swimming, shopping, etc.

Gun-ing Game (Arrow-ing Game)

The main action is pretending to shoot each other with imaginary guns in the classroom and the garden. They try to hide from each other to save their own lives. The gun-ing game evolved into an arrowing game, which will be further discussed in the following sections.

How do Children Construct Their Play?

The construction process of each game is unique and worthy of special attention. Although it is impossible to give a detailed account for each, a couple are chosen as examples. Each game was constructed at different times over the years, and the ideas underlying the games emerged from children’s imagination in the classroom. Typically, when a child introduced an idea and the other children liked it, the game would begin to evolve and eventually becames a living feature of the play culture of the classroom. The idea initiates the game construction process, and for a period, children negotiate the roles, rules, and responsibilities. There have been many other potential games that the children initiated, yet they faded away and were forgotten as ideas, as they were not accepted by all the children.

Each game has a specific name, and children refer to the game in this way. As soon as the game was invented, the first thing children did was name it. The games in the classroom were invented and constructed spontaneously by the children and are authentic to the Little Daisies Classroom.

The following are the examples of game construction processes taken from the field notes for the Naughty Child-ing Game, which was first constructed while Filiz and Can were playing together and acting out the roles of mommy and the child. The game was carried on for 1 year.

Filiz and Can are playing in the drama corner with an armchair and a kitchen for children. Filiz is acting as the mother, and Can is the baby. When the play starts, Can (the baby) sits in the armchair, and Filiz (the mother) cooks beside him. They constantly dialog with each other and discuss how the scenario will proceed.

Can tell Filiz, “Let us say I was lying in my bed, and you said good night to me. You were cooking in the kitchen, and I got out and ran away from my bed”. Filiz says, “OK,” with a smile on her face.

They listen to each other like they have a contract between themselves. Throughout the play, when Filiz pretends to recognize Can is out of his bed, she yells at Can, “I said go to your bed!”. She seems to be very tired and very busy in the kitchen. Can stops acting and says, “Wait, Filiz, you did not recognize me yet.” Filiz says okay and continues to cook as if unaware of Can's actions.

A similar pattern occurred with the Scooby Doo-ing Game. One day, the children sat around the table during snack time, and İrem talked about the cartoon, Scooby Doo. She said, “I love Shaggy a lot!” (referring to one of the characters in the cartoon). After this conversation, they looked at each other and agreed to play Scooby Doo. They started planning and imagining who would be who and which adventures they could have. They became very excited and immediately wanted to play. Later, when the PR asked them how they came up with this game, İrem replied: “I watched Scooby Doo a lot. It came to my mind”.

Another game spontaneously created by the children and became one of the unique features of the play culture of the classroom was the Cave-ing Game. Three small chairs are next to the wall in the drama corner. On this day, Osman and Filiz were crawling in front of the chairs. Osman wanted to put the chairs in front of each other and make a tunnel with them. He said, “Minecraft play has some caves; let me build the cave,” he started initiating the play. Minecraft is a kind of computer game about adventure and construction with a block-like appearance of the construction materials. When the others saw Osman building the cave, they came and surrounded him to watch and observe his preparation for the play. They called this play, the “Cave-ing Game.”

How do They Decide Who is Going to Play?

In the HighScope Plan process, as in Little Daisie's classroom, the teacher and the children sit on the carpet, form a circle, and take turns telling their plans for playtime. Children choose where and with whom to play when the first author asks them about their plans. They announce their plans at this phase; for example, “I want to play the Baby-ing Game.” The teacher asks others, “Who will join her?” Close friends prefer to play with each other to have fun together. For example, in the Naughty Child-ing Game, two close friends, Filiz and Can, preferred playing together. When they were asked individually about why they generally prefered playing with each other, they responded that it was because they liked playing together. Once, Filiz said: “I like playing with Can. He is so funny.” Filiz also has another close friend, Osman. She enjoys playing with Osman and likes to be his assistant in the Cave-ing Game, as she kept saying in the planning process: “I will be Osman’s assistant in the Cave-ing Play.”

By the end of school, Osman was becoming more popular among some of his friends. According to Asya: “Osman is so nice; I like to play with him,” and she purposefully wanted to play with him in his Cave-ing Game.

When children were passionate about particular games, their names became associated with those specific games. For example, Yaman enjoyed playing the Gun-ing Game. One could quickly tell his passion and devotion while playing the game, and the others wanted to play this game with him as well. They even suggested playing the Gun-ing Game with Yaman to one another. When asked why they called out Yaman’s name when they decided to play the Gun-ing Game, Emre said: “Because I like to play with Yaman in the Guning Game. He is so excited, and he plays well”.

On the other hand, in the Child-ing Game, there is room for just two children: the caregiver and the baby. Therefore, once two children formed the game, they would not let others join in their game. For example, one day, Yaman approached Can and Filiz and asked if he could play with them. They said, “It is our play, we found it, and this is a play for two only.”

When the PR asked them why, Filiz was quite principled in her decision and said that she wanted to play only with Can because this was their game, and they found it. That is why only they can play the Naughty Child-ing Game”. Based on the teacher/ researcher's observations, Yaman is an active child and generally does not prefer to follow the directions of his friends during play. Even though the scenario is about a baby acting out, there were specific rules each player should follow. These rules were predetermined and negotiated among Filiz and Can. Another interesting point about the Naughty Child-ing Game was that no other children ever attempted to join in or chose to play this scenario as if there was a silent agreement among them, which adults did not and might not know.

One day, when Yaman insisted on playing with Filiz and Can, the PR encouraged them to do so, and they allowed Yaman to join their game, but they did not let him behave like he wanted to. They tried to control his actions and reactions. Yaman wanted to be a naughty child and did not want to follow Filiz’s directions, who was pretending to be the mommy. Filiz and Can did not like that. Yaman began acting out and began to throw the toys and pillows around. Filiz raised her voice and said: “Yaman, you are out. The game is finished for you,” she left the play area. When the PR asked about what happened, Can said, “We do not want Yaman to ruin our play,” Filiz said, “Because Yaman ruined our play area, he did not sleep, and he did not listen to me. That is why I left because I was getting angry. I needed to calm down. I left the area, and the play was finished.”

How Do They Dismiss Players?

Children dismissed players due to two conditions: (1) interrupting the game flow and (2) not obeying the game rules. In the children’s play, they constructed an environment and would not let the others ruin it. For each play, they wanted to keep this environment safe to pursue their play. Anybody who did not comply with this rule was dismissed.

For example, in the Gun-ing Game, they pretended that the building blocks were guns and arrows. After they took their guns and arrows, they took them everywhere with them all the time. Breaking the arrows into pieces was forbidden; if someone did that, they needed to leave the game. Osman said that “ruining the arrows is not ok because arrows are special. We need to keep them safe.” Filiz replied, “We spent too much time making these arrows.” Other examples of ruining the game included harming toys, like cups, baby pillows, and mother’s tools in the Baby-ing Game. Whoever ruined these would be dismissed from the play.

The second reason someone would be dismissed from play was for not obeying the game's rules. As there were rules for each game, children who joined the game were required to follow them. If they did not, play members, particularly the “play builder,” reserved the right to dismiss these players. For example, in the Cave-ing Game, there is a rule for collecting treasure from the cave, a privilege granted to the “game builder.” If someone acts against this rule and collects the treasure, he or she is dismissed from the game without negotiation. In the Gun-ing Game, it was forbidden to spit. While making “chuff” sounds, children needed to be careful not to spit. Whoever spat by mistake or intentionally was dismissed. Moreover, if someone blocked his or her friend and forbade his/her actions and moves, he or she was also dismissed. One day, Emre tried to shoot, and Yaman blocked his vision. Emre got very angry and decided to dismiss Yaman from the game.

How Do They End the Play?

Children terminated games or stopped playing for three reasons: (1) reaching the goal in the play/satisfaction, (2) getting bored or seeing something more interesting, and (3) a time limit. A game was terminated when children seemed satisfied, which means that if a shared task was completed, children terminated the play. For example, in the Cave-ing Game, the play finishes when the children find the treasure. The play terminated once the monster was caught in the Scooby Doo-ing Game.

Boredom and distraction were other reasons for the termination of the games. The children ended their games when they got bored or saw something more interesting. Age seemed to be a significant factor in getting bored or distracted during play. The third reason for ending a game was the time limitations due to daily scheduling demands. As mentioned before, in the school where the research has been conducted, the play time was limited to one hour. Even this unrestricted one-hour time was not enough for children at times, as they wanted to keep playing some of the games for more extended periods. This was evident with Gun-ing Game in the Little Daisies Classroom. As children enjoyed hiding, shooting, escaping, chasing, crawling, and jumping, there was hardly an end to this play. Unfortunately, they often had to end the game because of the daily schedule.

Finally, when the children were unhappy about how the game proceeded, they reserved the right to terminate it. Particularly, if the game had a builder, he or she could terminate the game. For example, for the Cave-ing Game, Osman had the right to terminate it as the builder of the game. One day, Osman said, “The cave-ing game play is finished! OK, it is closed”. Similarly, while Filiz and Can were able to terminate the Naughty Child-ing Game, as they were the builders of the game, the other children generally accepted the decision and did not insist. The game termination right of the builder was another rule for the games in the classroom.

How Do Games Evolve (Into Other Things or Other Games)?

Over time, some games evolved into other games. For example, the Gun-ing Game evolved into the Arrow-ing Game due to the PR’s attitude towards guns, war plays, and violence in the classroom. As the PR expressed discontentment, the children did their best to convince the PR, saying, “This is not a real gun; this is an arrow. No smoke is coming out of it, and nobody dies.” The PR had to reinterpret personal worries and concerns and consider children’s voices. Once the consensus was reached between the PR and the children, the game proceeded as the Arrow-ing Game.

Another example is how Baby-ing Game Play evolved into subcategories such as “Ge ge no no Baby-ing Game” and “Mud Baby-ing Game.” In the game, there were roles of mommy and baby; however, one day, they said, “Babies cannot speak.” Following this conversation, one of the children, Osman, started uttering meaningless words like “ge ge, no no” as if it were how babies speak, and the children accepted it. After that, the Baby-ing Game evolved into another subcategory that children called “Ge ge no no-Baby-ing Game.” During another baby-ing game, children pretended to be the babies playing around and not listening to their mothers. At that time, one of the children pointed at the floor and said, “mud.” After that word, children around this area began jumping into the pretend mud. Children probably liked the mud idea because they imagined they would get dirty, which was funny for them. That day, when some said mud, they started laughing and jumping around the carpet. Osman, Filiz, and Asya used the word “mud” several times. After a few days, they named this “the Mud Babying Game” (çamur bebekçilik).

Room for Adults in Sociodramatic Play

Occasionally, the PR tried to participate in the children’s games by asking their permission to play. One day, Asya was sitting on a chair. Then she placed four chairs as if forming a square group in the middle of the classroom, and she took a pink plate in her hand and started holding it as if it was a steering wheel. The PR wanted to join in the game, and asked kindly:

PR: Can I play with you?

Asya: (smiling) Yes, where would you like to go?

PR: I want to go to the bookstore.

Asya used her steering wheel and made a car noise; in a few minutes, she told the PR, “We have arrived!”. She asked: “Teacher, do you want to play with me again or not.” PR said yes, and Aysa asked the PR again, “Where do you want to go?” The PR replied, “I am hungry.” Asya held the PR’s hand and took the PR next to the bookshelves. Asya got a small book, pretended to eat something from it, and said she was eating pizza. Then they pretended to eat together. After lunch, Asya returned to her driver's seat and asked the PR again, “Where do you want to go?” The PR said, “I want to go to the toy store." She stood up, moved next to the block corner, and showed the PR some toys. From now on, the driver started leading the play. She talked with an imaginary toy storekeeper and said it was expensive. She told the PR, “You are expecting a baby boy; this toy is for your baby boy.” The PR said thank you. At that moment, Beren was playing next to the block area and invited Asya to her play. Asya told Beren, “Now I am playing with my teacher.”

PR: Beren, would you like to play with us?

Beren (she did not want to listen to the PR and turned to Asya): Mommy! I want to sit next to my mommy.

She sat on the chair next to the driver seat, and Asya suddenly became a mommy driving a car and talking to her daughter about their plans: “Now, we will get some toys, and we will go to the park; trampoline, slide, swing, and I will get you earrings!” Beren smiled and said, "OK!" Asya turned to the PR asking, “Do you want to play more?” She gave the PR a soft duck toy and said, “Here is your baby!” as if she was trying to keep the PR busy because she seemed to prefer and enjoy playing with Beren more.

Beren and Asya were sitting on a big cushion together the other day. They were pretending to sleep. The PR came next to their cushion and knocked on the door. They opened the imaginary door, making the noise, “Clink!” They were talking about planning to go swimming and said, "Let us get ready. Beren turned to the PR and said, “Do not come!” Asya added, “We have an important job to do!”

When they accepted the PR into their play, they either assigned the PR secondary roles, tried to keep her busy in vain, or assigned the PR superficial or opposing roles, such as the teacher, thief, or monster. They treated the PR in ways that would keep her outside the play, such as forcing the PR to go to jail and being harsh.

Discussion and Conclusion

Play Culture of Little Daisies Classroom

In this study, the children of the Little Daisies Classroom developed their own unique play culture, which consists of shared experiences, knowledge, values, language, and ways of thinking (Kalliala, 2005). When playing the games they invented, such as creating a cave with chairs or a gun from Lego pieces, the children knew exactly what the game was, with specific rules and roles, and only allowed certain behaviors. This is what sets their play behaviors apart from mere pretending. Unlike other spontaneous dramatic play, the children had predetermined rules, roles, structure, and behaviors that were not to be challenged. Each time they played the game they created, only superficial changes were made to the storyline based on their daily experiences. For example, in the baby-ing game, one day, the mom might take the baby to a bookstore and another day to a pet shop. However, the scenario, roles, number of players, relationship dynamics, and how the mom treated the baby remained unchanged.

The children in the Little Daisies Classroom created games by living in the same classroom culture over the years and continued to play them as they shared the same classroom. The games remained unchanged, with the same scenarios, actions, roles, and sequences, yet the children never got bored or tired of playing them for years. The games were essential to the classroom's play culture and were driven by individual children's interests, likes, and strengths. Moreover, the games were joint products of the children in this classroom, bound by that specific time and context (Corsaro & Eder, 1990). Attending the same school and being in the same classroom for years led children to create this culture and helped them become more accustomed to it. While studying with different children would reveal different findings, studying with the same children at different times would also reveal different results. As the new sociology of childhood (James & Prout, 1997) posits, children's construction of their culture and experiences are meaningful, valuable, and worthy of attention for their own sake.

In the Little Daisies Classroom, children created their own culture by adapting the information they received from adults. This process, known as interpretive reproduction (Corsaro, 1992), involved negotiating their values, thoughts, and interests. They used their knowledge to interpret, construct, and reproduce their play culture within five games. Some of these games were based on real-life experiences, allowing children to practice their agency by role-playing and experiencing new scenarios. Imaginary worlds, computer games, or cartoons inspired other games. Through collective interpretation, children reproduced new "experiences" that formed a shared meaning with their group and peers (Corsaro, 2015). Play culture also allowed children to practice alternative roles other than their own. Every child involved in a game contributed their interpretation of their experiences, resulting in a collective reproduction of that small group's culture. Experiences were constructed by all active agents in that specific group.

Transactions among Sociodramatic Play, Agency, and Cognitive Maturation

Sirkko et al. (2019) highlighted that conceptualizing children's agency is a significant challenge that requires viewing it as independent of adult influences and constraints. To consider child agency authentic, it must solely reside within children. However, the context in which children live, such as the power dynamics of adults around them, ideological values, and the political climate in their community, all shape their agency. In the current study, it was evident that children were inspired by elements of their culture, such as conventional and moral values, family life, cartoons, armed conflict, etc. They used their imagination and negotiated as active agents to reproduce these elements in their games. Eventually, they created unique games as a product of their play culture.

Children in the Little Daisies Classroom developed their culture and improved their social, emotional, and cognitive abilities through socio-dramatic play and game construction. In their animal studies, Spinka et al. (2019) found that animals actively participate in unexpected play situations, which enhances their versatility of movements and emotional coping mechanisms. Similarly, the children in the Little Daisies classroom enjoyed playing games involving dangerous and unexpected situations, such as escaping from monsters or chasing gang members. According to Vandervert (2017), the cerebellum is responsible for training the brain to deal with the unexpected, and this mechanism is critical to socialization, play, and culture. Playing is not only fun but is also an "evolutionarily adaptive positive feedback loop" that drives the evolution of play towards culture and higher levels of intelligence.

During sociodramatic play in the Little Daisies classroom, children actively participate in their learning and development with power and agency. As they engage in sociodramatic play throughout their childhood, this creates a positive feedback loop between their tools, such as agency, power, developmental accomplishments, and executive functions. Both agency and the complexity of sociodramatic play are associated with cognitive advancements, particularly in executive functioning.

The prefrontal cortex is one of the fastest-growing regions of the brain, and experiences during the early years significantly impact its development. Early signs of executive functioning in children can be seen during infancy (Hartas, 2014a, 2014b; Hodel, 2018). Parent–child transactions and home environment impact the development of the prefrontal cortex in the earliest years, and later, the preschool environment also gains importance. Relationships with peers and play in the early childhood context are significant early environmental factors. Although executive functioning (EF) develops throughout childhood and adolescence, the early years lay the foundation for executive function skills. These skills are defined as children's ability to regulate their behaviors and emotions in a goal-directed fashion (Hartas, 2014a, 2014b; Hodel, 2018; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Luerssen and Ayduk (2017) argue that human agency is developed through peer interactions, which adults do not always organize. Children are often confronted with real-life challenges in social spaces, where they are expected to resolve them independently (p.64).

Children as Social Agents and Teachers as Facilitators

Children’s agencies have long been contested in research and have been elaborated in legal documents and cases. Even though it has been acknowledged across many disciplines, accepting agency in principle is not enough to realize this principle in practice (Punch, 2016). However, children must develop agency early on, especially within safe and familiar environments such as family and school. Socio-dramatic play provides an excellent opportunity for children to exercise and develop their internal and external forms of agency through play, interactions, dialogues, and conflict within a safe space surrounded by friends and adults. This helps them take ownership of their thoughts and actions, allowing them to guide their train of thought and behavior. (Baker et al., 2021).

In the Little Daisies Classroom, children engaged in sociodramatic play and game construction, which helped them develop their sense of agency in a supportive environment with their peers. The teachers play a significant role in creating a supportive environment for the children's agency by providing pedagogical tools, break times, and opportunities to learn new skills. The study found that the school curriculum, atmosphere, and the PR allowed children to move beyond sociodramatic play and create a more autonomous and self-driven play culture, as opposed to what is often observed in structured, teacher-led, activity-based, and teaching-focused early childhood settings.

Early childhood settings are great places for children to develop and practice their agentic skills. Children are encouraged to make decisions, exert power, and control their lives in these settings. Compared to higher grade levels, early childhood settings offer the most favorable environments for children's agentic rights (Sirkko et al., 2019). However, there are still significant variations in centers' philosophies, curricula, and physical and social settings, as well as they handle children's agency in the school environment, particularly in Turkey.

According to Garvey (1990), adults sometimes limit children's play. However, the findings of this study suggest that even when the teacher attempted to prevent children from playing with toy guns in the classroom, they still managed to play with them, albeit with some modifications. Breathnach (2017) pointed out that children explore their world through improvisation and recreation. This indicates that when children encountered environmental restrictions, they did not simply comply with adult directives and modify their behavior. Instead, they found ways to negotiate and convince the teacher to let them play their game. They explained that the guns were not real and that they were merely using them for pretend play. They also claimed that the guns were water guns or fake. When their explanations failed, they adapted their game using arrows instead of guns. Despite this modification, they still played a pretend armed conflict, chasing each other and enjoying their game.

Teacher beliefs and attitudes are crucial in early childhood education as they can significantly impact children's learning and development (Clark & Peterson, 1986). While some teacher behaviors can positively support and empower children by allowing them to exercise their agency, some beliefs and practices can pose challenges. In the Little Daisies Classroom, the PR supported and encouraged children's sociodramatic play, enabling them to practice their agency. She provided children with ample space, time, and resources and even positioned herself in ways that allowed children to assign her roles or even keep her away from them. However, we also noticed that some of her beliefs challenged the children. For instance, the PR openly disapproved of children playing with toy guns, even though building blocks were used as pretend guns. Heart and Tannock (2013) suggest that some practitioners believe playing violent games can lead to aggressive behavior in children, while others think that such play fosters social, emotional, and cognitive development by allowing children to express their aggression or practice engaging in dangerous and unexpected situations (Vandervert, 2017). Although the teacher's attitude towards guns challenged the children, it did not deter them from playing the game. Instead, it allowed them to negotiate with the teacher and convince her that their tools were toys, not weapons. We noticed that the teacher's beliefs that challenged the children's play enabled them to exert their agency, but this was only possible because PR listened to the children and allowed them to negotiate.

A recent study demonstrates that when children can play with their peers and have control over their environment and the chance to influence adult behavior, they develop strategies to solve problems, regulate their emotions and behavior, and collaborate with adults. According to Baker et al. (2021), this approach to learning is consistent with how children's brains naturally learn. Allowing children to be willing participants in their learning journey fosters a sense of agency, and as they practice their agency, they become self-motivated learners. This creates a positive feedback loop, with more robust mechanisms leading to greater agency and more effective learning.

It can be inferred that children require ample opportunities to develop and express their agency through sociodramatic play, where they engage with their peers in the classroom and broader community and create tangible objects such as rule-based games.

Implications

Sociodramatic play is full of potential for young children to empower agency and enrich experiences related to developmental areas. However, there are specifics aspects needed preschool teachers to set their priorities. To begin with, teachers need to take children’s sociodramatic play seriously and understand its worth and consequences for children’s current and later development. Providing unrestricted time for play for at least one hour daily is a vital criterion for nurturing socio-dramatic play. Likewise, arranging the classroom via learning centers, materials, and props that can be used in socio-dramatic play is vital for encouraging sociodramatic play for children. Children need to feel free; therefore, allowing children to contribute to change in the classroom organization is another condition for nourishing socio-dramatic play.

Moreover, observing children to find ways to enhance sociodramatic play and engaging in systematic observation to discover children’s routines, cultural practices, and customs within the classroom can help teachers enrich children’s sociodramatic play. Engaging in discussions during circle times or large group discussions can also make children feel empowered and encouraged.

Finally, sociodramatic play can reveal valuable knowledge about children, so teachers need to review their curricular goals and objectives and reconsider how they can meet them through sociodramatic play.

Limitations of the Study

A significant limitation of this study is that it is qualitative and was conducted with only ten children within a single context. Therefore, the findings are specific only to the Little Daisies Classroom. Additional research in a quantitative tradition could reveal more comprehensive and enriched results.

References

Abebe, T. (2019). Reconceptualizing children’s agency as a continuum and interdependence. Social Sciences, 8(3), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030081

Baker, S. T., Courtois, S. L., & Eberhart, J. (2021). Making space for children’s agency with playful learning. International Journal of Early Years Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1997726

Breathnach, H. (2017). Children’s perspectives of play in an early childhood classroom. PhD by Publication, Queensland University of Technology.

Clark, M. C., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 255–296). Macmillan.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2007). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage.

Corsaro, W. A. (1992). Interpretive reproduction in children’s peer cultures. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 160–170.

Corsaro, W. A. (1997). The sociology of childhood. Pine Forge Press.

Corsaro, W. A. (2015). The sociology of childhood. Sage.

Corsaro, W. A., & Eder, D. (1990). Children’s peer cultures. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 197–220.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Danbolt, G., & Enerstvedt, Å. (1995). Når voksenkultur og barns kultur møtes: en evalueringsrapport om de kulturformidlingsprosjekter for barn som Barnas hus, Bergen, har satt i gang. Norsk kulturråd

Deunk, M., Berenst, J., & De Glopper, K. (2008). The development of early sociodramatic play. Discourse Studies, 10(5), 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445608094215

Dinham, J., & Chalk, B. (2018). It’s arts play: Young children belonging, being, and becoming through the arts. Oxford University Press.

Edwards, C. P. (2000). Children’s play in cross-cultural perspective: A new look at the six cultures study. Cross-Cultural Research, 34(4), 318–338.

Garvey, C. (1990). Play. Harvard University Press.

Goldman, L. R. (1998). Child’s play: Myth, mimesis and make-believe. Berg.

Hardman, C. (1973). Can there be an anthropology of children? Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, 4(2), 85–99.

Hartas, D. (2014a). The social context of parenting: Mothers’ inner resources and social structures. Research Papers in Education, 30(5), 609–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.989177

Hartas, D. (2014). Critical reflections on early ıntervention. In D. Hartas (Ed.), Parenting, family policy, and children’s well-being in an unequal society. Palgrave Macmillan studies in family and ıntimate life. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137319555_6

Hodel, A. S. (2018). Rapid infant prefrontal cortex development and sensitivity to early environmental experience. Developmental Review, 48, 113–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.003

Hughes, B., & Melville, S. (2002). A playworker’s taxonomy of play types. Playlink.

James, A., & Prout, A. (1997). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary ıssues in the sociological study of childhood (2nd ed.). Falmer Press.

James, A., Jenks, C., & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Wiley.

Kalliala, M. (2005). Play culture in a changing world. Open University Press.

Karabon, A. (2016). They’re lovin’ it: How preschool children mediated their funds of knowledge into dramatic play. Early Child Development and Care, 187(5–6), 896–909.

Lester, S., & Russell, W. (2008). Play for a change: Play policy and practice- a review of contemporary perspectives. Play England.

Lindqvist, G. (2001). When small children play: How adults dramatize and children create meaning. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 21(1), 7–14.

Luerssen, A., & Ayduk, O. (2017). Executive functions promote well-being: Outcomes and mediators. In M. D. Robinson & M. Eid (Eds.), The happy mind: Cognitive contributions to well-being (pp. 59–75). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58763-9_4

Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among pre-school children. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27(3), 243–269.

Punch, S. (2016). Exploring children’s agency across majority and minority world contexts. In F. Esser, M. Baader, T. Betz, & E. Hungerland (Eds.), Reconceptualizing agency and childhood: New perspectives in childhood studies (pp. 183–196). Routledge.

Schweinhart, L. J., & Weikart, D. P. (1981). Effects of the perry preschool program on youths through age 15. Journal of the Division for Early Childhood, 4(1), 29–39.

Schweinhart, L. J., & Weikart, D. P. (1988). The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program. In R. H. Price, E. L. Cowen, R. P. Lorion, & J. Ramos-McKay (Eds.), Fourteen ounces of prevention: A casebook for practitioners (pp. 53–65). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10064-005

Sirkko, R., Kyrönlampi, T., & Puroila, A. M. (2019). Children’s agency: Opportunities and constraints. International Journal of Early Childhood, 51(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00252-5

Smilansky, S. (1968). The effects of sociodramatic play on disadvantaged preschool children. Wiley.

Smith, P. K., & Pellegrini, A. (2008). Learning through play. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, 24(8), 61.

Špinka, M. (2019). Animal agency, animal awareness and animal welfare. Animal welfare, 28(1), 11–20.

Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Thyssen, S. (2003). Child culture, play, and child development. Early Child Development and Care, 173(6), 589–612.

Tuğrul, B. (2018). Early childhood education in Turkey. In Handbook of International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education (pp. 70–84). Routledge.

Vandervert, L. (2017). Vygotsky meets neuroscience: The cerebellum and the rise of culture through play. American Journal of Play, 9(2), 202–227.

Wolcott, H. F. (1987). On ethnographic intent. In G. Spindler & L. Spindler (Eds.), Interpretive ethnography of education: At home and abroad (pp. 37–57). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wolcott, H. F. (1994). Transforming qualitative data: Description, analysis, and interpretation. Sage.

Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Development Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00246.x

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yesil, R., Erdiller Yatmaz, Z. & Metindogan, A. Exploring Children’s Play Culture and Game Construction: Role of Sociodramatic Play in Supporting Agency. Early Childhood Educ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01621-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01621-5