Abstract

The overall aim of the present study is to describe and explore the characteristics and content of school social worker’s (SSWs) individual counselling with children as these are imprinted in session protocols collected at Swedish elementary schools. Specific focus is placed on the character of the children’s concerns, the content of the SSW’s helping strategies, and challenges related to the alliance between the SSW and the children as experienced by the SSW. The study was based on data from a survey protocol of 20 SSW’s daily practice regarding their experiences in counselling children and adolescents. The data consisted of 193 protocols from the same number of unique individual sessions. Data were analysed through quantitative descriptive statistics. The data also contained a large proportion of open-ended textual answers, which were analysed through a qualitative summative content analysis. The counselling strategies were primarily divided into three parts, namely coaching, processing, and assessing. The most common practice elements used included elements of empowerment, alliance and relationship, and hope and trust. In counselling children, SSWs identified a broad range of problems in children’s overall lives. Many children suffered from their home situations, which also impinged upon the SSWs, who were affected by the children’s life narrative. Our results can help inform SSW policy and practices as SSWs assist vulnerable children through individual counselling that corresponds to their help-seeking behaviour and by offering a space for alliances and relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Internationally, research on school social work, counselling and children’s concerns in school and life in general is increasing. The core of school social work is usually described as psychosocial support to children and adolescents, who for various reasons suffer from different concerns such as mental ill-health, school absenteeism or stress, which make them unable to achieve their intended goals in school and life (Huxtable, 2022; Rafter, 2022). An earlier Swedish study (Kjellgren et al., 2022) states that School Social Workers (SSWs) preferably meet these children in individual counselling sessions. However, there is a lack of knowledge about the situation in Sweden regarding both the characteristics of the help-seeking children, and the strategies and practice elements used by the SSWs in counselling. The concrete features of the counselling practice are of certain interest, as there are no clear directives or guidelines regarding expected professional content formulated by national actors in Sweden, nor are there any requirements for holding records of the children attending counselling. Therefore, the chosen Swedish case can be used as an illustration of how school social work is formed in the absence of specific regulations.

Childhood Risk Factors

Childhood can be challenging, and adolescence is an exposed and vulnerable period with an increased risk of developing risk behaviours and mental ill-health (Blodgett & Lanigan, 2018; Salokangas, 2021). Several different studies have indicated increased mental ill-health for children and adolescents and have found that 10–20% experience clinically significant concerns that require timely assessment and adequate interventions (Colizzi et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2012; Lemberger & Hutchison, 2014; Vostanis et al., 2013).

School-related factors of the psycho-social environment—including peer-relations, safety, social status, interpersonal relationships, stress and workload—can be contributory factors to mental ill-health (Huxtable, 2022). The Global Burden of Disease project (Mokdad, 2013) reports an upward trend in depression and anxiety, especially in teenage girls. In a study on differences between boys and girls regarding self-reported school-related stress, Högberg and Horn (2022) found that girls reported higher levels of school-related stress, although not significantly higher. Skipper and Fox’s (2022) study from the UK focused on whether schools had different expectations for boys and girls. The results revealed differences that implied more negative impact on boys, in terms of bullying and disengagement from school. Teachers were treating boys and girls (unintentionally) differently. The classroom situation in secondary school also contributed to the immense pressure on young people to conform to gender stereotypes.

Family-related adversities, such as neglect, domestic violence, poverty, divorce, homelessness and various family traumas affect a large number of children in the course of their learning (Blodgett & Lanigan, 2018; Huxtable, 2022) and there is a correlation between neglect and poor school performance (Maguire et al., 2015; Porche et al., 2016). Exposure to adverse childhood experiences is a risk, but not a guarantee that concerns will arise (Blodgett & Lanigan, 2018).

School-Based Support

In accordance with international research, Swedish researchers (Gustafsson et al., 2010; Bortes et al., 2022; Kjellgren et al., 2022) and authorities (Skolverket & Socialstyrelsen, 2016, p. 13f (The Swedish National Agency for Education (NAE) and The National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW))) have reported how parental function and capacity are related to the concerns and mental health of children. This relation is connected with the child’s potential of performing and learning. Children have the right to grow up and feel safe, to increase their confidence, and to be provided with conditions that facilitate the achievement of school knowledge goals (Swärd, 2020; SFS, 2010, 800). Moreover, children should receive guidance and stimulation from the school to develop and mature as optimally as possible (SFS 2010, 800, 1 chapter 4§, 3 chapter 2§); the school has to provide support to families for the child's upbringing and development, i.e., social goals.

Maguire et al. (2015) suggest that social care staff (Social services and/or SSWs) should be aware of children who need their help and should make plans for adequate support. The SSW, as a psycho-social specialist in the school, is expected to analyse and understand the child’s vulnerability (Rafter, 2022). Alvarez et al. (2013) states that the knowledge and skills that SSWs bring to the schools can lead to better educational outcomes for the children. By paying attention to, supporting, and strengthening the child, school failures can be prevented (Porche et al., 2016).

Internationally, the SSW is described as a multifaceted profession (Huxtable, 2022; Sosa et al., 2016); most prominently, the function is described as a link between different school professions, the school and other actors such as social services, and the school and the children’s home. Foremost, the SSWs meet children in their current life situation. Beddoe (2019), Lyon et.al. (2019) and Pendley (2021) promote the idea that SSWs can contribute to taking the lead and supporting multi-professional teams, so-called pupil health teams (PHT), in determining how to assist children at risk in order to prevent school failure. In Swedish pupil health teams (PHT), different professions are represented, including nurses, physicians, psychologists, special educational teachers, and SSWs (Hjörne & Säljö, 2014; SFS, 2010:800).

In total there are about 2600 SSWs in Sweden, who are primarily employed through local municipalities. Most hold a bachelor degree in social work, and 12–14% have basic training in psychotherapy. On average, each SSW has approximately 300–800 pupils in their catchment area (Novus, 2021). Often, the SSWs share their time between a number of schools (SKR, 2021; Kjellgren et al., 2023; Guvå & Hylander, 2017). Even though there is an increasing amount of research on Swedish school social work, it foremost focuses on profession jurisdictional and organisational perspectives (Backlund, 2007; Isaksson & Larsson, 2017; Jansson et al., 2022), while the SSWs’ counselling practice and the children attending counselling are less described. Novus (2021) states that 75% of Swedish SSWs point out that an increased number of children are in need of support and that 76% of their work is remedial and emergency driven. Another study (Kjellgren et al., 2023) shows similar results, were the participating SSWs estimated that they worked on average 60–70% with remedial work and 30–40% with prevention. Individual sessions with children were included in both categories and therefore represented 80–90% of the work tasks.

Counselling Children

According to Jordans et al. (2013), counselling is defined as a planned and skilled interaction between the counsellor and a client with the overall aim to improve the client´s wellbeing. The counsellor makes use of a variety of counselling strategies and practice elements such as problem assessment and formulation, stress reduction, plans of action, coping strategies, social support, psychoeducation and processing trauma, if necessary. Research by Agresta (2004) and Huxtable (2022) shows that SSWs and counsellors spent substantial time on individual counselling. Internationally, there is an ongoing development of an evidence-based practice regarding school social work, supported by guidelines produced by professional organisations or federal authorities (Horton & Prudencio, 2022; Kelly et al., 2015; Staudt et al., 2005). Pincus et al. (2021) refers to American School Counsellors Associations´ (ASCA) recommendations on a variety of counselling strategies regarding different child concerns, e.g., adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) requiring a strategy of trauma-informed care in counselling and when counselling children diagnosed with ADHD, a coaching strategy is most helpful (Branscome et al., 2014). Swedish authorities (NAE and NBHW) describe the SSWs’ individual counselling as “professional counselling, such as supporting, motivating and crisis counselling as well as assessment of and processing with individual pupils and their families” (Skolverket & Socialstyrelsen, 2016). These types of counselling are, however, not further described in guidelines. From a previous study (Kjellgren et al., 2022), we learned that SSWs in Sweden embrace an eclectic counselling approach. Common practice elements such as empowerment, resilience, alliance, building trust and relationships are frequently used but without following or implementing evidence-informed guidelines or methods.

The Present Study

The overall aim of the present study is to describe and explore the characteristics and content of SSWs’ individual counselling with children as these are imprinted in session protocols collected at Swedish elementary schools. Four specific research questions are posed:

-

What are the characteristics of children enrolled in SSW counselling?

-

What are the concerns among the children and how are counselling contacts initiated?

-

Are there any differences according to gender and age, when receiving counselling?

-

What do the SSWs’ concrete helping strategies consist of and what can be seen as the practice elements in these strategies?

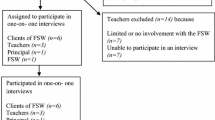

Twenty SSWs were asked to fill out a protocol after each counselling session with a child. In total, 193 session protocols related to the same number of unique children were completed. To come close to the everyday practice of the SSWs, the study design consists of a combination of both quantitative and qualitative data, based on real cases of individual sessions.

Method

Participants

Our intention with this study was to recruit a group of SSWs that could represent a broad spectrum of experiences. To cover different basic prerequisites, we selected four geographical areas in Sweden: two metropolitan areas, one large city and one rural area covering the southern, mid, and northern parts of the country. Principals, school social work coordinators, and pupil health teams managers in the four areas were then identified and contacted to help us distribute information about the study. Information about the study was also distributed on the website “Skolkurator.nu” (Association for Swedish School Counsellors). Participation implied taking part in a qualitative focus group interview study and a protocol study. The results from the focus group interview study are reported elsewhere (Kjellgren et al., 2022, 2023). Because of the design of focus group interviews, the maximum number of participants was set to about 30 SSWs. At the end of our recruitment period of three months, 25 people agreed to be part of the study, but due to a lack of time or sickness, five of them dropped out before start. A total of 20 SSWs participated in the protocol study: twelve respondents worked as SSWs in metropolitan areas, three respondents in middle-sized towns, and five in rural areas. The participants were all locally employed in municipal elementary schools and working with children aged 6–16 years. In Sweden, elementary school for children between 6 and 16 years of age is mandatory, while preschool for children 1–5 years of age and upper secondary school for adolescents 16–19 years of age is voluntary. The SSWs had a variation in age and previous occupational activity (on average 16 years of practice in school social work, ranging from 3 to 42 years). All respondents held a higher basic education (Bachelor of Social Work) or post-secondary education (i.e., basic psychotherapy education, 4 out of 20 participants). In addition, 17 out of 20 participants were women, which corresponds to the overall division of men and women in school social work in Sweden.

The European Code of Conduct for Research (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017) was followed during the research process. Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained both verbally and in writing. Participants were assured that the protocols were handled with secrecy and were anonymous with a code number to protect information on the individual child as well as the individual SSW.

The project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-04934). No potential conflict of interest is reported by the authors.

Procedure and Measurement

In the absence of an appropriate and validated measurement, we created a protocol that was based on a number of adequate questions according to the research aim. The purpose was to gather detailed and concrete data of the individual counselling performed by SSWs. The protocol was fist submitted as a draft to the SSWs and tested through a co-production-approach among the participant group of 20 SSWs. Feedback was then received from the same 20 SSWs, who contributed with concrete suggestions on the final design of the protocol. Their feedback included for example, what the SSWs considered as common or typical concerns among children and counselling strategies and practice elements often used by SSWs in counseling contacts. Finally, the protocol was critically analysed and adapted by the three co-authors, as well as validated by the same participant group of 20 SSWs. The final version of the protocol contained 28 questions (19 closed questions and nine open-ended questions) divided into four core clustered sections, namely Case characteristics (five questions), e.g., gender and age of the child, and reason for initiation; Type of contact (ten questions), e.g., the child’s initial and additional concerns, as well as the counselling strategies (overall strategy) and practice elements (specific techniques) used by the SSW in the counselling contact; and Reciprocity and relationships (six questions), e.g., the child’s and the SSWs’ physical and mental availability and speaking space. Lastly, one set of questions (seven questions) focused on the SSWs’ role, e.g., factors that facilitated or hindered the counselling and reflections on the SSWs’ counselling practice. We used the SSWs’ own concepts on type of contact and counselling strategies. Closed questions included a mix of nominal questions (including multiple choice questions) and ordinal questions (Likert scales). The majority of the variables were on an ordinal scale, and all variables at the ordinal scale level were constructed with a centre option.

As a complement to the closed questions and to facilitate in-depth answers, all four clustered sections (described above) included open-ended questions. For example, when answering an identified change for the child, a question “If ‘yes’, in what way have you noticed change with/within the child?” followed in the protocol. After answering questions about impingement factors for the SSW, a complementing question was asked: “Can you identify general factors that affected or influenced you in this specific case (-Which? -How?)”.

The protocol was distributed in a paper version to the SSWs. Each SSW also received instructions on how to handle and complete the protocol and they then submitted handwritten responses. They were asked to complete one protocol for each of the first ten individual counselling sessions with children during a three-month period in spring 2020. In total, 193 protocols (sessions with 193 unique individuals) were completed and returned. Two of the SSWs returned eight protocols each, and one SSW returned seven protocols, which means a total drop-out of seven protocols. There were some internal missing data in the question on speaking space (n = 189). With that exception, the 193 returned protocols were completely filled out. All SSWs responded to the open-ended questions. The gathering of data took place at the beginning of the Covid pandemic; however, all Swedish elementary schools were exempt from the lockdown and remained open. The open-ended questions did not reveal any information on the influence COVID might have had on the children or possibilities for the SSWs to arrange modified counselling strategies.

This was a cross-sectional study, and all data were collected during the same time period. The protocol is far from all-encompassing, but it enabled the gathering of data from a purposely selected studied population (SSWs). The sample is insufficient in size to be representative of all SSWs in Sweden, but as described, we have made efforts to select informants from different geographical areas and schools with a variety of sociodemographic features.

Procedure/Data Analysis

The analysis of the data was completed section by section, following the structure of the protocol, where each section´s primary focus corresponded to the research questions. Each section consisted of both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 26.0). Children’s characteristics such as gender and school year are central variables. School years are divided into three categories in compliance with school years in the Swedish elementary school (1–3, 4–6 and 7–9). Characteristics connected to a range of variations to the central variables, such as degree of concerns and areas of concerns as well as information about the initiator of the actual case, were analysed using descriptive statistics (Hatcher, 2013) in terms of frequencies (n) and proportions (%). The areas of concerns were further stratified by school year and gender. Counselling strategies and practice elements were analysed in a similar way including frequencies and proportions with 95% confidence intervals.

The four clustered sections consisted primarily of quantitative, fixed-answer- questions (see explanation above) but each section also included open-ended questions with free-space answers. The open textual answers were analysed through a qualitative directed content analysis (Hsieh et al., 2005). All answers were first transferred to a Word document and organised by their manifest content, following the headings in the protocol. As a second step, thematic categories were identified under each heading. Thereafter, a hierarchy was created based on the counting of all meaning units identified connected to each category. For example, under the protocol-heading “Initial motive for contact”, the created category “family relations” was found to have the highest number of meaning units and was therefore placed as the top-category. Discussions were held between the three co-authors to identify categories, and to ensure and enhance credibility. The analysis was conducted entirely in Swedish, and the extracted themes then translated into English by the researchers. A professional English language reviewer was also included in this process. Relationships between the quantitative and qualitative data were also reviewed and triangulated to enhance the understanding of the material.

Results

Results are presented in five sections: (I) Case characteristics, (II) Initial and additional concerns in focus, (III) Counselling strategies, (IV) Practice elements and (V) Reciprocity and Relationship.

Case Characteristic

This section addresses the first three research questions concerning the characteristics of children enrolled in SSW counselling. The children and adolescents (n = 193) that attended the sessions were all enrolled in Swedish municipal elementary schools and were 6–16 years of age in school years 1–9, divided into 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9. The case characteristics are presented in Table 1. Forty-nine percent of the children were in school year 7–9 (n = 94) (13–15 years of age) and there was a slight dominance of girls in the data (n = 112, 59%). Three dominating initiators were identified: a parent (n = 49, 27%), a teacher (n = 46, 25%), or the child itself (n = 45, 25%). A teacher was most often the initiator for children in school years 1–3 (6–9 years of age); a parent was the most common initiator for children in school years 4–6 (10–12 years of age); and the children themselves were the most common initiators in school years 7–9. The severity of the child’s concern was assessed by the SSW on a four-grade scale (low, moderate, severe, and very difficult), and in a majority of the cases, the severity was assessed as moderate (n = 68, 36%) or severe (n = 62, 33%), altogether representing 69% (n = 130).

Initial and Additional Concerns in Focus

The following section addresses the second and third research questions, focusing on concerns among children and how the counselling contact is initiated. Regardless of school year or gender, home situation (n = 61, 32%), relational problems (n = 57, 30%), and anxiety (n = 49, 25%) emerged as the three most common initial concerns. Firstly, to answer the third research question, we analysed areas of concern based on gender (Fig. 1). The concerns for girls were consistent between different school years (in total): home situation (n = 38, 34%), relational concerns (n = 43, 38%), and anxiety (n = 31, 28%). In comparison, the concerns for boys were more diverse, where, for example, extrovert behavioural concerns appeared as the overall most common concern. Secondly, we divided the groups of children according to age (school year) to be able to answer the third research question. In school year 1–3, home situation (n = 7, 39%), extrovert concerns (n = 5, 28%), and class-related concerns (n = 4, 22%) occurred most frequently. The situation changed in school year 4–6 and became a mix of extrovert concerns (n = 4, 18%), behaviour concerns (n = 5, 23%), other concerns (n = 6, 27%), and neuropsychiatric concerns (n = 5, 23%). For the oldest boys (school year 7–9), anxiety (n = 14, 37%), depression (n = 10, 26%), home situation (n = 10, 26%), and stress (n = 8, 21%) dominated.

The textual answers also showed a connection between what the child expressed and communicated about the concern and what the session focused on. Concerns with their home situation seemed to leave the strongest imprint on the SSWs. The textual answers uncovered aspects such as divorces and conflicts between parents and the SSWs interpretations of how the children were affected. Such issues were related to different arenas of the child’s everyday life, including both its individual and social life.

Counselling Strategies

The SSWs registered a wide range of sessions in counselling contacts with each child (1–180 sessions, M = 16, Md = 8) over different time periods (1–240 weeks, M = 33, Md = 20).

Types of strategies are presented in Fig. 2. This result section addresses the third and fourth research questions concerning what the SSWs concrete helping strategies consist of and what can be seen as core practice elements in these strategies. All strategies appeared in all school years. Overall, there was a clear emphasis in the results on ‘coaching’ as counselling strategy (n = 75, 39%). The results also reveal that ‘coaching’ is the dominant SSW strategy for children in school years 4–6 and 7–9 when receiving counselling. However, the results did not reveal what type of coaching the SSWs were referring to. ‘Processing’ was the second most used (n = 36, 19%) counselling strategy and the dominant strategy with children in school years 1–3. ‘Assessment’ as a strategy (n = 35, 18%) was evenly divided across the school year, whereas ‘Treatment’ (n = 21, 11%) was primarily used in counselling contacts with children in school years 7–9 in combination with ‘Coaching’.

Practice Elements

This result section addresses the third and the fourth research questions. The most frequently used practice elements during the sessions were building an alliance and relationship with the child (n = 84, 44%), empowering the child (n = 76, 39%), and offering hope and trust to the child (n = 66, 34%) (Table 2).

The SSWs were asked to mark 1 to 3 practice elements used in each session. When analysing the use of strategies and practice elements during different types of contacts, the results showed that in the ‘Coaching’ strategy the most common practice element was alliance/relationship (n = 33, 44%), followed by empowerment (n = 30, 40%). When involved in the ‘Processing’ strategy, the most commonly used practice element was hope and trust (n = 19, 54%) followed by empowerment (n = 17, 49%). In the ‘Assessment’ strategy, the most frequently used practice element were alliance/relationship (n = 22, 61%) and motivation (n = 12, 33%), while the most frequently used practice elements in ´Treatment´ was empowerment (n = 11, 52%) followed by psychoeducation (n = 10, 48%). In ‘Crisis counselling’, practice elements for crisis coping were used (n = 8, 47%) together with hope and trust (n = 7, 41%).

In conclusion, the results confirmed that the alliance/relationship was the most frequently used practice element and the first-hand choice in two out of five types of counselling strategies. Empowerment appeared in five out of six counselling strategies and hope and trust emerged in three counselling strategies.

Reciprocity and Relationship

This result section addresses the fourth research question. In the textual answers, the SSWs described dealing with sensitive topics from different angles. It seemed that the SSWs strived to follow the path that the children determined. The SSWs also described in several cases that both parties were engaged, knew each other well, and had a good and trustful relationship.

The protocols establish the two dimensions of availability—mental and physical availability—of the SSW and the child and reflect how the SSWs estimated the level of reciprocity between them and the children. A vast majority of the SSWs estimated their mental availability to the child as either good (n = 98, 50.8%) or very good (n = 70, 36.3%). In the textual answers, the SSWs described that when children accepted counselling, the physical presence was the most important factor, i.e., that both parties were able to attend. A high degree of presence, focus, and active listening to the child's narrative was then required, as well as an empathic commitment and relation-building focus. Some SSWs described that an excessive workload and stress reduced their mental availability. A majority of the SSWs assessed the mental availability of the child as, at a minimum, good.

The physical availability of the SSWs was essentially rated as good (n = 79, 41%) or very good (n = 51, 26%), which was clarified in the textual answers by those SSWs who were physically present at school by having specific days booked as well as offering new sessions to the child in advance. All appointments were carefully booked, planned, and prioritised. About a third of the SSWs described their physical availability as neither high nor low. Both contexts were reported in the textual answers citing situations such as few working hours at one school, a nomadic life between schools, and/or fully booked schedules. Nonetheless, the SSWs struggled to find time to help the individual child. Two-thirds of the SSWs rated the child’s physical availability in the session as good (n = 63, 33%) or very good (n = 59, 31%), thus confirming the textual answers of the children as eager and wanting to attend sessions. In contrast, some of the children often forgot sessions and needed a reminder or did not want to leave tutored classes but preferred sessions to be booked outside the daily class schedule.

Just over half (n = 101, 53%) of the SSWs estimated that the speaking space was divided equally between the SSW and the child. In about one third of the cases, the child had the dominant speaking space (n = 55, 29%), and in the rest of cases it was the SSW who used the most space (n = 33, 18%).

According to the SSWs’ textual answers, reciprocity was mentioned as the prerequisite and creation of a working alliance, where a close relationship was created, stressing the importance of mutual collaboration and cooperation. In 131 of 193 cases, the SSWs declared that the children had improved in relation to the initial formulation of concern during their SSW contact. The textual answers contained descriptions that revealed that the SSWs estimated children’s participation in the process of change and their ability to describe their life situation and feelings as higher and more nuanced than initially (n = 34). Moreover, the SSWs perceived the child as calmer (n = 24), with changed behaviour (n = 14), and that the child’s relations were improved (n = 13). Furthermore, the improvement of the child manifested itself through expressions such as being happier, more relieved, more open, more confident, and more talkative. Despite descriptions about vulnerability and mental ill-health, there were also a number of optimistic and hopeful remarks among the SSWs on relating and expressing the child’s present and narrow future.

Discussion

This study reveals some interesting findings on elementary school social work in a context where the profession lacks guidelines, and the practice is rather unregulated. An earlier study (Kjellgren et al., 2023) suggests that national guidelines for SSWs should be developed. To our knowledge, individual counselling with children is a common and established task for Swedish SSWs, yet there is no previous research on who these children are or what takes place in the counselling sessions. This lack of knowledge has inspired this paper. Considering our results, a “typical” case would be a girl, initiating contact by herself, having moderate to severe concerns regarding her home situation and relationships while also struggling with anxiety. She meets the SSW in counselling, and the SSW adopts a coaching or treatment strategy. The SSW makes use of practice elements such as an building alliance/relationship, empowerment, and psychoeducation.

Counselling Strategies and Practice Elements

Considering the features in SSW counselling, e.g., what helping strategies the SSWs apply in individual sessions, our results afford indications, i.e., that ‘coaching’ and ‘processing’ are the most frequently used while ‘treatment’ is the least common. However, uncertainty regarding what these strategies consist of remains. Considering our design, to make use of rather undefined concepts for categorising strategies established by the NAE and NBHW (2016), commonly referred to in professional practice, it is uncertain whether the SSWs categorised the strategies routinely or with critical reflection. A reflection, based on a common idea among SSWs in Sweden that treatment should not be conducted in the school context, is that contradictions between the idea and what they do might create doubts concerning what school social work is (and is not). Such ideas and doubts might contribute to censoring or downsizing the actual frequency of ‘treatment’.

The analysis of practice elements is more substantial, providing a more narrowed and concrete picture of what the SSWs actually engage in during sessions. Alliance and relationship, empowerment, hope and trust, guidance and psychoeducation emerged as prominent and can thus be seen as core practice elements. These elements also occur as common factors or are embedded in the common factors model (Frank & Frank, 1991) for creating a healing situation in psychotherapy and counselling, which is promoted by Baskin and Slaten (2014) as an appropriate framework in school counselling. Further, the present study indicates that Swedish SSWs have a rather long counselling relationships with the child. Ferguson et al. (2022) highlight the therapeutic holding function in a long-term counselling relationship and the healing value of such relationship.

The core practice elements can also be understood as an eclectic approach consisting of rather common counselling skills. This seems rather reasonable considering the diversified group of children and wide range of concerns appearing in SSW counselling. Further, the counselling is delivered in the school setting and as part of the pedagogical pledge. One of the most important protective factors is for a child to complete the formative school years in order to enter adolescence and adulthood (Porche et al., 2016). Therefore, a prominent task of social experts at schools should be to identify and meet these children in an adequate manner in order to facilitate their individual development. This reflects the importance of the readiness to meet children of different ages and life situations and the ability to identify and apply contextually appropriate practice elements. In other words, having the flexibility to, from a psycho-social perspective, adjust to the child’s vulnerability (Rafter, 2022).

Characteristics of Children and Their Concerns

In school years 1–3, the initiator was often the teacher, which seems fairly reasonable because the teachers are usually the sole teacher and thus possesses good knowledge of the child. Allen et al. (2021) points out that the teacher’s role is included in a pedagogic and dynamic approach to caring and wellbeing, and a positive relationship is included in the teaching process itself. We can assume that such caring factors motivate the teacher to seek further help for the child when necessary. Processing counselling is mostly offered, which seems reasonable considering the young age of the children. Polites et al. (2010) state the inevitable challenges for early childhood professionals to promote the safety of the child when expressing their feelings in order to renew a sense of trust and restore hope regarding their future. Another possible explanation for processing could be that younger children cannot handle concrete advice on how to solve concerns by themselves, i.e., there is a necessity for adult parental and/or professional back-up. Thus, in early school years, children need to be able to talk and to have somebody who listens in order to develop social-emotional competence. However, the results do not show in which way SSWs offer more concrete assistance to the youngest age group.

In school years 4–6, parents were most often the initiators, which might be explained by the fact that they have an increased awareness of the child’s life in school both through school itself as well as the child’s own capacity for expression. The results indicated a higher prevalence of concerns regarding behaviour (extroversion) and neuropsychiatric indications within this group compared to the other groups (Fig. 1). The relationship between behavioural concerns in school and possible neuropsychiatric difficulties has been discussed in previous research. Taneja Johansson (2021) notes that elementary school is not designed for all children and that the transition to middle school means a radical change for them. Harwood and Allan (2014) points out that school-related concerns are solved by pathologising the individuals and thus avoiding the challenge of dealing with organisational concerns. The respondents in Taneja Johansson’s (2021) study on the school experiences of children with ADHD reported that middle school was a turning point that included a lack of relationship with teachers, a lack of study skills, and difficulties understanding expected behaviour and what was required to be achieved during the lessons. Research shows that adverse childhood experience is associated with behaviour concerns, lack of impulse control, and concerns of executive function, which may appear similar to ADHD (Brown et al., 2017; Overmeyer et al., 1999; Timimi & Timimi, 2022). Our results show that the group of boys in years 4–6, in addition to behavioural difficulties, displayed indications of neuropsychiatric concerns that are also highly rated together with home situational concerns. Further, girls in this age group are described by the SSWs in this present study as having a combination of concerns regarding their home situation, relational problems and anxiety. Overall, this age-group appears vulnerable in the sense of their concerns but with significant potential to recover. When it comes to the group in years 4–6, regarding our study, there seems to be a smoother working relationship between the child and the SSW, with coaching as the most common counselling strategy and defined goals for improving life concerns.

Lastly, in school years 7–9, children themselves were the most common initiators, most likely due to increased maturity, autonomy, and capacity for analysis and reflection. In addition, in this school year children often have the capacity to identify, understand and verbalise life concerns such as family relations, mental illness, addictions, and other adversities. Interestingly, our study indicates that boys’ extroverted behaviour does not persist during school years 7–9 and that anxiety, depression, and home situation concerns predominate. For girls, the three dominant and consistently reported areas of concern remain home situation, relational concerns, and anxiety. In the later school years, depression also increases for girls. Their concern focus is of a more intrapsychic nature, which could imply feelings of resignation (Williams & Nida, 2022). In counselling contacts with children in secondary school, SSWs provide more treatment, with practice elements such as empowerment and psychoeducation. By shifting practice element, the SSWs seem to prepare the oldest children for a life outside elementary school (and without a relation with an SSW) by supporting children’s’ self-awareness and emotional growth.

So, in total, we can see a shift, with an increased number of children initiating a counselling contact themselves as they grow older. In accordance with previous research (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2019; Huxtable, 2022; Maguire et al., 2015), the results of our study conclude that children who attend counselling with SSWs do so primarily in order to receive support regarding their home situation and relational concerns, wide areas that are not specified nor deepened further in the results. Kelly et al. (2015) also states that SSWs work with children who are exposed to high levels of risk, including mental health problems and behavioural concerns. The results of this present study do not offer any explanation for boys’ or girls’ different areas of concerns. The SSWs identified that girls have three dominant and consistently reported areas of concern, and in later school years, depression increases. For boys, the areas of concern varied between school years, and frequently reported concerns, such as home situation, were manifested differently between boys and girls. Therefore, gender-based concerns and its manifestations would also be relevant to disseminate further. Primarily, this would contribute to a better understanding of boys’ behaviour and how to offer adequate counselling. Secondly, it would also offer a better preparation for SSWs on differences that are common between boys and girls, which they will likely encounter in counselling sessions.

When analysing what children bring to SSW counselling, we found a quite wide variation of concerns that can be seen as grounds for emotional strain. The SSWs in our study do not meet, to any great extent, children with a focus on school related concerns, such as difficulties in reaching knowledge goals or learning difficulties. It may be reasonable to assume that some of the intrapsychic concerns that the SSWs recognise as initial concerns, such as anxiety, stress and depression may have a school related connection. Our study only highlights the psycho-social impact of emotional strain in general and does not reveal any specific cause of the stress and/or anxiety of the child. A recent study (Högberg et al., 2021) indicates that the Swedish grading system has a negative impact on children’s mental health. The results from our study could thus imply that emotional strain is caused by study or grade issues, but it might also depend on home conditions and/or the children’s relationships with family and/or peers or all factors combined. According to the SSWs, the prominent focus of concern was family-related concerns. Even though the analysis in our study cannot establish a statistical relationship between home situation and individual intra-psychological mental ill-health (stress, anxiety, and worries), the textual answers in the protocols offer some support for this relation. Kelly et al. (2015) highlights the importance of providing direct service to a child and to include the family as well as community support.

In addition, our results also shed some light on the professional challenges and burdens connected with addressing children’s concerns in individual counselling. The SSWs seem to be mentally affected and impinged upon, and these challenges should be paid attention to because compassion fatigue can easily affect social workers who handle difficult situations (Page, 2021; Paterson et al., 2021). The availability for a child to receive individual counselling from an SSW is affected by a combination of the number of children in the school district as well as the broad range of different work tasks that are expected of them. It is also affected by the SSWs’ degree of knowledge. According to Kelly et al. (2015) SSWs need in-depth skills and knowledge regarding these complex work tasks. Despite the above situation, SSWs prioritise individual help-seeking children, and regardless of having a full agenda, the SSWs keep contact, remind, and arrange for the child to attend counselling (Kjellgren et al., 2022). Kelly et al. (2015) conclude that SSWs are identified as the most appropriate professional group to deliver remedial support in school-based settings.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The intention of this study was to shed light on SSWs’ own experiences regarding their individual counselling practice. The session protocol was designed for this particular study and formed in collaboration with the SSWs who received an early version that they could comment on. The strength consists of a protocol with questions and themes close to the informants every-day practice. The results are thus grounded in real student cases, rather than the SSWs’ general thoughts and reflections, and provide insights into the SSWs´ counselling practice. However, the choice not to use already existing and validated measurements constitutes a weakness in relation to generalisability and comparability. The data in this study are not based on a stratified random sampling, which consequently makes the statistical analysis difficult to interpret and generalise in any way to a larger population.

Another limitation is the exclusive SSW perspective used in the study, through whom all protocols were filtered. With that said, it is reasonable to believe that case-oriented individual interviews could have provided deeper knowledge from each individual participant. However, our experience is that the protocols were filled with great ambition. Our strategy to use one protocol for one specific case/child, and to ask the SSWs to fill them out in direct relation to the individual sessions, can bring more precision to the data compared to surveys or interviews with broader and retrospective questions about their overall experience of counselling practice.

The relationship between different initial reasons (concerns) for counselling contact did not appear as expected. A possible explanation is that only two alternatives could be selected in the protocol, for example, questions about counselling strategies and different kinds of practical elements. This might have forced the SSWs to select more unrelated alternatives when there were more than two suitable options.

Finally, in this study we tried to gather SSWs from different geographical areas and school districts and with a variety of experiences in regard to aspects such as gender, age and level of specialisation. Despite what we think is a relatively representative selection of Swedish SSWs, we have not used the mentioned variables actively in our analysis in this article, but instead considered the participants as part of one broad group. This lack of comparison between subgroups, for example, SSWs in rural versus metropolitan areas or participants with different degrees of experience and expertise, limits the analytical range of the study.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies conducted with Swedish SSWs about their concrete counselling practice with unique children, which must be considered as one of the prominent strengths of the study. The present study aimed to describe and examine SSWs’ experience with emphasis on the characteristics of their individual counselling sessions with children, which also is the overall contribution of the study.

Conclusions

Despite an increased amount of international research and knowledge on SSW counselling and concerns for children and adolescents, such as mental ill-health, adverse childhood experiences and peer-relational concerns, there is still a lack of research on the Swedish SSWs’ counselling practice, role, and function in relation to the focus of concern of the child. The SSWs´ work is mainly on a remedial level in individual counselling. The present study indicates that children attend counselling with concerns rated by the SSWs as moderate or severe. The main concerns that occur for girls are home situations, relational concerns, and anxiety. For boys, the main concern is manifested through a disparate pattern of misbehaviour. The SSWs’ counselling strategies are mainly carried out as coaching, processing, treatment, and assessment with the use of practice elements such as empowerment, alliance and relationship, and hope and trust. A major part of the SSWs highlight the positive results of counselling because children communicate improvements in their areas of concern. The findings stress the importance of assisting the vulnerable children in reaching their knowledge goals and supporting their social and emotional growth.

Recommendations for Practice, Policy, and Research

In our study of School Social Workers providing individual counselling in Swedish elementary schools, we learned three key things: (1) children that come to SSWs bring a wide range of concerns with them into counselling (2) the counselling performed by the SSWs is varied regarding characteristics, strategies and practice elements (3) receiving individual counselling is correlated with an improved well-being in children. These findings reflect the advantages of individual SSW counselling but also, the urgency of preparing national guidelines for school social work. More research is needed to evaluate the SSWs’ individual counselling and articulate best practice in school social work in order to inform policy and practice through evidence.

Data Availability

Due to the data being personal and given under a promise of anonymity, data used to support the findings of this study are not available on open access.

References

Agresta, J. (2004). Professional role perceptions of school social workers, psychologists, and counselors. Children & Schools, 26(3), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/26.3.151

Allen, K. A., Slaten, C. D., Arslan, G., Roffey, S., Craig, H., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2021). School belonging: the importance of student and teacher relationships. In M. L. Kern & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 525–550). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_21

Alvarez, M. E., Bye, L., Bryant, R., & Mumm, A. M. (2013). School social workers and educational outcomes. Children & Schools, 35(4), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdt019

Backlund, Å. (2007). Elevvård I grundskolan: Resurser, organisering och praktik. Stockholms Universitet.

Baskin, T. W., & Slaten, C. D. (2014). Contextual school counseling approach: Linking contextual psychotherapy with the school environment. The Counseling Psychologist, 42(1), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012473664

Beddoe, L. (2019). Managing identity in a host setting: School social workers’ strategies for better interprofessional work in New Zealand schools. Qualitative Social Work, 18(4), 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325017747961

Blodgett, C., & Lanigan, J. D. (2018). The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly., 33(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000256

Bortes, C., Nilsson, K., & Strandh, M. (2022). Associations between children’s diagnosed mental disorders and educational achievements in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948221089056

Branscome, J., Cunningham, T., Kelley, H., & Brown, C. (2014). ADHD: Implications for school counselors. Georgia School Counselors Association Journal, 21(1), 1–10.

Brown, N. M., Brown, S. N., Briggs, R. D., Germán, M., Belamarich, P. F., & Oyeku, S. O. (2017). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis andeverity. Ambulatory Pediatrics : THe Official Journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association, 17(4), 349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013

Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A., & Ruggeri, M. (2020). Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

Ferguson, H., Warwick, L., Disney, T., Leigh, J., Cooner, T. S., & Beddoe, L. (2022). Relationship-based practice and the creation of therapeutic change in long-term work: Social work as a holding relationship. Social Work Education, 41(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1837105

Folkhälsomyndigheten [Public Health Agency of Sweden]. (2019). Skolbarns hälsovanor i Sverige 2017/18: grundrapport. [Health Behaviour in School-aged Children]

Frank, J., & Frank, J. (1991). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gustafsson, J. E., Allodi Westling, M., Alin Åkerman, B., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., Ogden, T., & Persson, R. S. (2010). School, learning and mental health: A systematic review. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Health Committee.

Guvå, G., & Hylander, I. (2017). Elevhälsa som främjar lärande. Om professionellt samarbete i retorik och praktik. Studentlitteratur.

Harwood, V., & Allan, J. (2014). Psychopathology at school: Theorizing mental disorders in education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203071007

Hatcher, L. (2013). Advanced statistics in research: Reading understanding and writing up data analysis results. Shadow Finch Media LLC.

Hjörne, E., & Säljö, R. (2014). Analysing and preventing school failure: Exploring the role of multi-professionality in pupil health team meetings. International Journal of Educational Research, 63, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.09.005

Högberg, B., & Horn, D. (2022). National high-stakes testing, gender, and school stress in Europe: A difference-in-differences analysis. European Sociological Review, 38(6), 975–987. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac009

Högberg, B., Lindgren, J., Johansson, K., Strandh, M., & Petersen, S. (2021). Consequences of school grading systems on adolescent health: Evidence from a Swedish school reform. Journal of Education Policy, 36(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1686540

Horton, K. B., & Prudencio, A. (2022). School social worker performance evaluation: Illustrations of domains and components from the national evaluation framework for school social work practice. Children & Schools, 44(4), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdac016

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Huxtable, M. (2022). A global picture of school social work in 2021. International Journal of School Social Work. https://doi.org/10.4148/2161-4148.1090

Isaksson, C., & Larsson, A. (2017). Jurisdiction in school social workers’ and teachers’ work for pupils’ well-being. Education Inquiry, 8(3), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2017.1318028

Jackson, C. A., Henderson, M., Frank, J. W., & Haw, S. J. (2012). An overview of prevention of multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Public Health, 34(1), i31–i40. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr113

Jansson, P., Evertsson, L., & Perlinski, M. (2022). Skolkurator sökes—skolhuvudmäns beskrivning i platsannonser av skolkuratorns uppdrag, arbetsuppgifter, organisation, kvalifikationer och färdigheter. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 28(3), 289–312. https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2021.28.3.4263

Jordans, M. J. D., Komproe, I. H., Tol, W. A., Nsereko, J., & de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2013). Treatment processes of counseling for children in South Sudan: A multiple n = 1 design. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(3), 354–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9591-9

Kelly, M. S., Thompson, A. M., Frey, A., Klemp, H., Alvarez, M., & Berzin, S. C. (2015). The state of school social work: Revisited. School Mental Health, 7(3), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9149-9

Kjellgren, M., Lilliehorn, S., & Markström, U. (2022). School social worker’s counselling practice in the Swedish elementary school. A focus group study. Nordic Social Work Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2022.2041467

Kjellgren, M., Lilliehorn, S., & Markström, U. (2023). Therapist, intermediary or garbage can? Examining professional challenges for school social work in Swedish elementary schools. International Journal of School Social Work. https://doi.org/10.4148/2161-4148.1102

Lemberger, M. E., & Hutchison, B. (2014). Advocating student-within-environment. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 54, 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167812469831

Lyon, A. R., Whitaker, K., Richardson, L. P., French, W. P., & McCauley, E. (2019). Collaborative care to improve access and quality in school-based behavioral health. Journal of School Health, 89(12), 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12843

Maguire, S. A., Williams, B., Naughton, A. M., Cowley, L. E., Tempest, V., Mann, M. K., Teague, M., & Kemp, A. M. (2015). A systematic review of the emotional, behavioural and cognitive features exhibited by school-aged children experiencing neglect or emotional abuse. Child: Care, Health & Development., 41(5), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12227

Mokdad, A. H., Forouzanfar, M. H., Daoud, F., Mokdad, A. A., El Bcheraoui, C., Moradi-Lakeh, M., Kyu, H. H., Barber, R. M., Wagner, J., Cercy, K., Kravitz, H., Coggeshall, M., Chew, A., Steiner, C., Tuffaha, M., Charara, R., Al-Ghamdi, E. A., Adi, Y., & Murray, C. J. L. (2016). Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet, 387(10), 2383–2401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6

Novus (2021). Kartläggning skolkuratorer. https://akademssr.se/dokument/novusundersokning-skolkuratorer-2021 [Survey SSWs]

Overmeyer, S., Taylor, E., Blanz, B., & Schmidt, M. H. (1999). Psychosocial adversities underestimated in hyperkinetic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(2), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00439

Page, D. (2021). Family engagement and compassion fatigue in alternative provision. International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1938713

Paterson, B., Taylor, J., & Young, J. (2021). Compassion fatigue and behaviours that challenge in the classroom. Scottish Educational Review, 53(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1163/27730840-05301003

Pendley, M. (2021). School social work leadership. Self-efficacy and perceptions of multidisciplinary collaboration. Walden University.

Pincus, R., Ebersol, D., Justice, J., Hannor-Walker, T., & Wright, L. (2021). School counselor roles for student success during a pandemic. Journal of School Counseling, 19(29), 1–10.

Polites, A., Kuchar, K., & Bigelow, S. (2010). Hope and healing for children affected by domestic violence. Child Care Information Exchange, 191, 76.

Porche, M. V., Costello, D. M., & Rosen-Reynoso, M. (2016). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. School Mental Health., 8(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9174-3

Rafter, J. (2022). Revisiting social workers in schools (SWIS)–making the case for safeguarding in context and the potential for reach. Journal of Children’s Services. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-04-2021-0015

Salokangas, R. K. (2021). Childhood adversities and mental ill health. Psychiatria Fennica, 52, 10–13.

SFS (Swedish Code of Statues). 2010:800. Ny skollag (The education act). Utbildningsdepartementet (Ministry of Education)

Skipper, Y., & Fox, C. (2022). Boys will be boys: Young people’s perceptions and experiences of gender within education. Pastoral Care in Education, 40(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2021.1977986

Skolverket och Socialstyrelsen [The Swedish National Agency for Education and The National Board of Health and Welfare—NAE & NBHW] (2016) https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/vagledning/2016-11-4.pdf (Guide for pupil health team)

Sosa, L. V., Cox, T., & Alvarez, M. (Eds.). (2016). School social work: National perspectives on practice in schools. Oxford University Press.

Staudt, M. M., Cherry, D. J., & Watson, M. (2005). Practice guidelines for school social workers: A modified replication and extension of a prototype. Children & Schools, 27(2), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/27.2.71

Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner. SKR. [Swedish municipals & regions] (2021). Nuläge och utmaningar i elevhälsan 2021. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner. Retrieved July 7, 2022 from https://webbutik.skr.se/sv/artiklar/nulage-och-utmaningar-i-elevhalsan-2021.html

Swärd, S. (2020). Barnkonventionen i praktisk tillämpning: Handbok för socialtjänsten. Andra upplagan. Norstedts juridik.

Taneja Johansson, S. (2021). Looking back on compulsory school: Narratives of young adults with ADHD in Sweden. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 26(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2021.1930904

Timimi, S., & Timimi, Z. (2022). The dangers of mental health promotion in schools. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12639

Vetenskapsrådet [The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity]. (2017). Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning. Vetenskapsrådet.

Vostanis, P., Humphrey, N., Fitzgerald, N., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2013). How do schools promote emotional well-being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x

Williams, K. D., & Nida, S. A. (2022). Ostracism and social exclusion: Implications for separation, social isolation, and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101353

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University. The research was funded by the municipality of Åre and Umeå University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to disclose was reported by the authors.

Ethical Approval

The project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019–04934).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kjellgren, M., Lilliehorn, S. & Markström, U. School Social Work in Sweden—Who are the Children in Counselling, and What Support are They Offered? A Protocol Study About Individual Counselling in Elementary Schools. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00943-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00943-y